by Lorena Tota.

Abstract

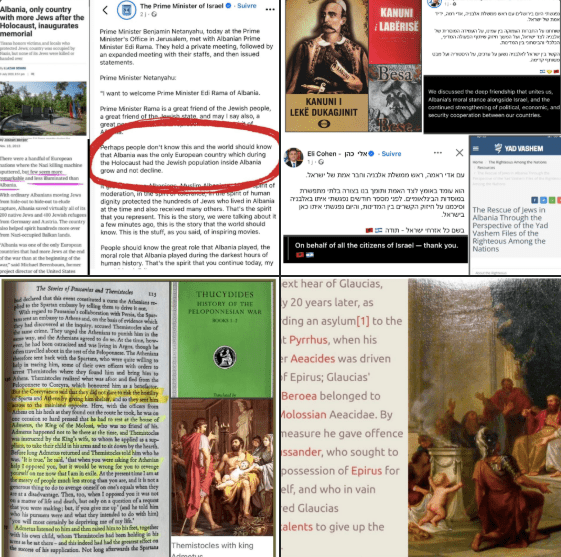

This text explores the historical continuity of the Albanian ethical principle of asylum, emphasizing its primacy over hostility and political expediency. From antiquity to the modern era, it traces a moral tradition rooted in honor and protection, illustrated by the sheltering of Themistocles by King Admetus and the rescue of the infant Pyrrhus by King Glaucias. These acts, predating formal legal systems, reflect an unwritten moral code later institutionalized in the Kanun through the concept of besa. The study further highlights the survival of this principle during the Holocaust, when Albania uniquely protected and increased its Jewish population. Together, these examples reveal a rare civilizational continuity in which hospitality and asylum function as foundational, non-negotiable ethical imperatives.

From Antiquity to the contemporary era, a single principle runs through the history of Albanian populations: the absolute primacy of asylum over hostility.

When Themistocles, a political enemy pursued by Athens and Sparta, sought refuge with Admetus, king of the Molossians, the latter refused to surrender him despite intense pressure, invoking a rule superior to vengeance and raison d’état: one does not strike a man who has fallen, and a guest placed under protection becomes inviolable.

This act, attested by Thucydides, was neither a matter of cunning nor of political opportunism, but the expression of a moral code predating classical written law, grounded in honour and the obligation of protection.

Again later we are informed of the infant Pyrrhus sheltered by his relative Glaucias, king of Taulanti who rejected an immense sum of money offered by Cassander in exchange for Pyrrhus. The Homeric code of Besa underpinned Glaucias resolution in saving Pyrrhus from certain death.

Centuries later, this same principle would be formalized in the Kanun under the concept of besa, binding the one who grants it to protect the guest even at the cost of one’s own life.

Far from being a folkloric survival, this ethical system manifested itself with remarkable consistency into the darkest hours of the twentieth century: during the Holocaust, Albania was the only country in Europe where the Jewish population increased, not as a result of exceptional heroism, but because the protection of the stranger was understood as a deeply internalized social duty.

Thus, from the courts of Admetus and Glaucias to Albanian villages under Nazi occupation, a rare moral continuity emerges, that of a civilization in which asylum is neither negotiable nor conditional, but constitutes a foundational imperative.