by Lulzim Osmanaj

A Comparison with the Celts and Northern Peoples

Abstract

This article examines nineteenth-century European interpretations of the Illyrians within the broader ethnological and cultural framework of prehistoric Europe. Drawing primarily on the work of Rudolf Hörnes, it situates the Illyrians as an autochthonous population predating later Slavic and Germanic migrations. The study contrasts Illyrian Hallstatt material culture with the La Tène Celtic world, emphasizing differences in aesthetics, metallurgy, and social values. While acknowledging the evolutionist and typological biases of nineteenth-century historiography, the article argues that these interpretations remain valuable for understanding early scholarly conceptions of Illyrian identity and their perceived role in the formation of Europe’s prehistoric ethnological landscape.

The Illyrians in the Ethnological and Cultural Context of Prehistoric Europe

In nineteenth-century European historiography, particularly in the works of scholars such as Rudolf Hörnes, the Illyrians were described as one of the earliest and most deeply rooted populations of Southeastern Europe, standing in clear contrast to northern peoples who arrived in the region at a later stage.

From this perspective, the Illyrians represented an autochthonous ethnic stratum, formed and consolidated prior to the major migratory movements that characterized later periods of European history, especially Slavic and Germanic expansions (Hörnes, Urgeschichte der Menschheit).

The text emphasizes the chronological distinction between Illyrians and Slavs, portraying the latter as late arrivals from the north who, due to geographical and historical circumstances, remained largely confined to peripheral regions.

Within this framework, decisive historical significance is attributed to populations already present in the territory during key moments of Central and Southeastern European cultural and political development. This interpretation reflects the evolutionist approach typical of nineteenth-century historiography, in which chronological precedence was often equated with historical legitimacy.

The Illyrians are further characterized through a distinct anthropological and cultural profile. They are depicted as shorter in stature, darker in pigmentation, and frequently tattooed—features that distinguished them from the Celtic and Germanic populations of Central Europe.

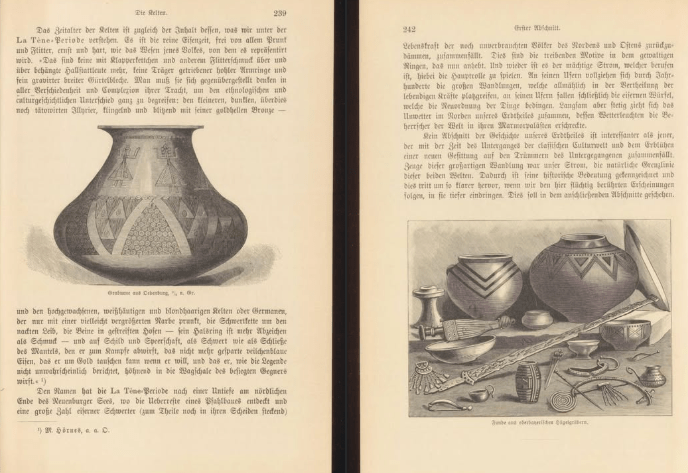

Illyrian dress and material culture are marked by the extensive use of bright bronze, abundant ornaments, and a pronounced tendency toward decoration, traits associated with the Hallstatt cultural tradition. These elements suggest a society in which visual symbolism and adornment played a significant role in expressing social status and identity.

In contrast, the Celtic world of the La Tène period is presented as a new ethnological and aesthetic phase, characterized by simplicity, austerity, and individualism. Celts and Germanic peoples are described as tall, light-skinned, and fair-haired, dressed in more functional and less decorative attire.

Their ornaments, such as the neck ring (torques), functioned primarily as symbols of honor and status rather than as aesthetic embellishments. Iron, the dominant material of this culture, replaced Illyrian bronze and became emblematic of a martial and ascetic mentality that valued strength and discipline over visual splendor.

In this context, the La Tène period—named after the settlement on the northern shores of Lake Neuchâtel—represents not merely an archaeological style but a profound social and cultural transformation. Numerous discoveries of iron swords and enameled objects testify to a world in which warfare, honor, and military symbolism occupied a central position. This shift marks a clear departure from older Illyrian traditions and a reorientation of ethnic forces in Europe.

Nevertheless, the text suggests that the Illyrians did not simply disappear in the face of this transformation but instead constituted a deep historical layer upon which later developments were built. The role of major rivers as natural boundaries and as arenas of historical confrontation is highlighted as decisive in this process, presenting them as witnesses to the transition from the classical world toward a new European civilization. In this way, the Illyrians emerge as an integral part of this heritage, a foundational element in the ethnological mosaic of prehistoric Europe.

In conclusion, the portrayal of the Illyrians in this text reflects a combination of archaeological data, anthropological interpretations, and the historiographical ideology of the nineteenth century. Although some elements must today be approached with critical caution due to the romanticism and ethnic typologization of the period, the text remains significant for understanding how the Illyrians were conceptualized as an early, autochthonous, and culturally distinct people in European history.

References

Hörnes, R. (1892). Prehistory of Mankind. Vienna: AlfredHölder.Basteiner, A. (elaborations on prehistoric European ethnology).

Collis, J. (2003). The Celts: Origins, Myths and Inventions. Stroud: Tempus.

Harding, D. (2007). The Iron Age in Northern Europe. London: Routledge.