Abstract

This text explores the emergence of republican consciousness in Kosovo through the perspective of childhood memory. By combining personal recollection with historical events surrounding the 1981 protests, it demonstrates how political ideas were transmitted through social rituals, student activism, and everyday acts of symbolic resistance. The narrative reveals how repression intensified creativity and how national identity was internalized at an early age, framing the Republic not as an abstract demand but as a lived and shared experience

I remember March 8, 1981. I remember it in every detail—both the date and the event.

I was thirteen years old. At the wedding there were three rooms for guests. At one moment the music stopped, and in one of the rooms everyone began to gather. The doorway filled with curious people who wanted to hear the words of a wise man, well dressed, dignified. When he smiled, his white teeth cast a gentle light around him.

“For the sake of this wedding, Uncle Xhemë—Mother Zade loved you very much,” he said, rising from his seat, removing the white cap from his head, and embracing him warmly.

Halil Alidema told the wedding guests to continue the singing, because the in-laws, as custom demands, wished for meat, drink, and song. Then he continued:

“May God bless this house that has been honored with so many friends. This has always been a noble household. My grandmother told me about Uncle Beq, about the mill that never stopped its water or its stone!”

“Speak, Halil, you are in the house of the Zogjans. The night is long for celebration until morning,” my father told him.

The silence was broken by his resonant voice. His shining eyes, the whiteness of the cap slipping onto his jacket, his chest and tie began to sway.

“We know that we are an oppressed people. We know how many skins we have lost under regimes. After the fall of Aleksandar Ranković there were improvements and easings, but we must not stop here. One step forward, one mattress, must not deceive us. We must learn to demand equality with other peoples, with the other republics of Yugoslavia.”

The mention of the word “Republic” was followed by immediate applause, which erupted and dissolved the iron discipline that had previously ruled. Someone outside fired a few pistol shots. Halil nodded to the host, placed the cap back on his head, and then the song began:

Dardania beats a drum,

the wedding guests arrive with white caps.

It was not a song from musical groups, but from students. It was unclear whether they had coordinated. Halil Alidema announced the spring. Three days later, on March 11, 1981, in the streets of Prishtina, the demand for the Republic of Kosovo emerged from drawers, beginning its historic journey.

It was not easy to write “Kosova Republic” everywhere. This phrase was monitored by state security guards. The acronym KR was simpler; it could be written quickly and everywhere. It could also be “erased” by hand.

We wrote it in notebooks with pencil, erased it, then wrote it again and erased it again. Sometimes we forgot to erase it. When we wrote it with indelible pencil, the paper had to be torn or scribbled over so it wouldn’t show.

We wrote it and scribbled it again, covering it repeatedly.

We wrote it with chalk. Later, at school, we were not allowed to take chalk ourselves. Teachers had to fetch it, leaving the lesson unfinished. We wrote it in sand, near the Morava River. Dry sand, not wet, looked better—more convincing, more serious. It was art. When the sand was refined and compacted, the letters remained like metal letters until broken by the sun or crushed underfoot.

Often we wrote it in snow. If we stayed too long, our fingers went numb and we warmed them with our breath. We wrote it with the tip of a compass—on chairs and desks. Once, when we wrote it on the classroom door, they removed the door and took it away for analysis to determine who had written it. We were told the police would come to find the authors. The door never returned.

The hardest was writing with lime. The lines were difficult to make clear. Someone wrote with purchased paint. The letters were beautiful. We did not know who was writing, but we saw who was erasing.

A classroom game—lightly throwing chalk to land it in the pocket of a uniform—was fun and harmless. One piece of chalk flew higher and struck the frame on the wall of Comrade Tito.

“Oh, oh, oh…” began the chorus of classmates who feared we might be beaten, or that something worse could happen. A piece of chalk on Tito could cause a major political problem.

We wiped the chalk mark with the classroom sponge. Fear faded and calm returned. Concentration on the lesson softened under the heat of the stove burning coal and wood. The rising heat caused the sponge marks to dry white. Tito turned white, with a white beard, looking like Father Winter. Some laughed, others felt uneasy. The teacher had not noticed.

When the bell rang and the teacher left, we reached the photograph and wiped it with our sleeves, spitting a little to clean it better. Tito regained his shine. We, “his pioneers,” with red scarves, wrote K.R. behind the photograph in rebellion—and quickly erased it.

Students of the Republic.

Xhevat Xh. Latifi

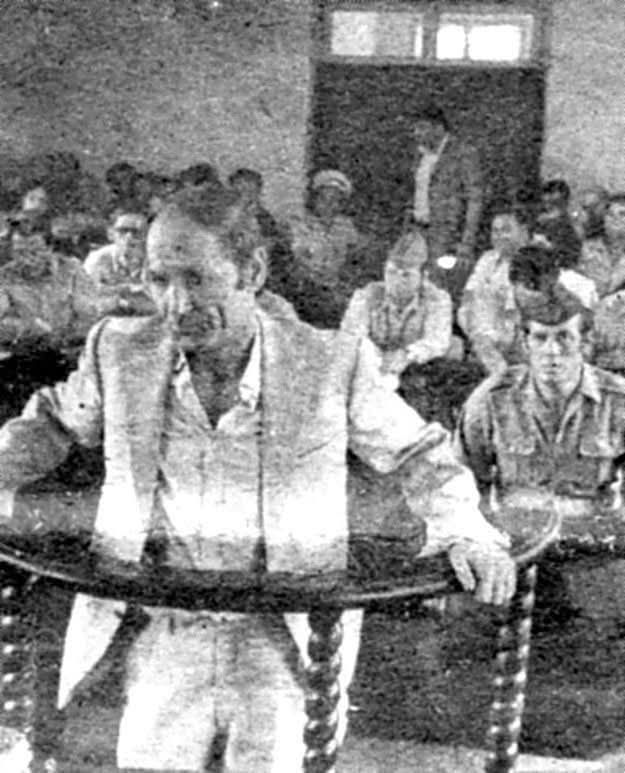

Photo: Halil Alidema, from Wikipedia.org