by Lulzim Osmanaj.

Abstract

This study re-examines the ethnic identity of the Triballi by critically analyzing ancient literary sources and modern historiographical interpretations. It argues that the Triballi were part of the central Illyrian cultural and geographical sphere and that later classifications as Thracian or Dacian result from terminological fluidity and anachronistic readings. The article highlights the need for a contextual and methodologically consistent approach to ancient ethnonyms and identity formation.

This article discusses the Triballi and Scordisci, The Getae–Dacian–Triballi Confusion and the Distortions of Modern Historiography

The Triballi represent one of the most complicated cases of Balkan ethnogenesis in ancient sources. They are frequently mentioned by Greek and Roman authors, but rarely in a uniform or coherent manner. Depending on the author, political and geographical context, the Triballi have been described sometimes as Illyrians, sometimes as Thracians, sometimes as Getae or Dacians.

This terminological pluralism does not necessarily reflect a multiple ethnic reality, but rather the way in which ancient authors conceived and described the world around them. The aim of this essay is to analyze the Triballi in the context of ancient sources and to highlight later distortions, both ancient and modern, arguing that they belonged to the central Illyrian space, similarly to the Scordisci.

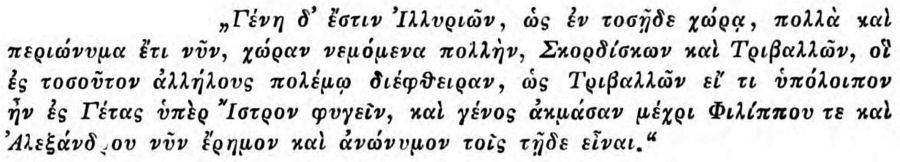

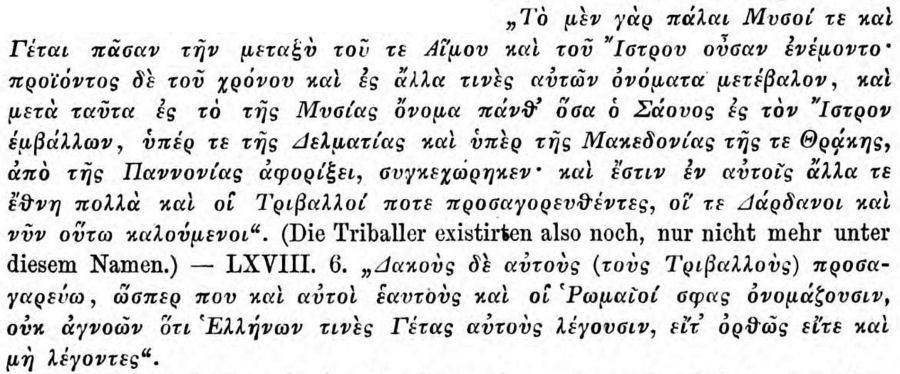

Ancient authors did not understand ethnicity as a biological or unchanging category, but as a fluid reality, linked to territory, power and political reputation. Strabo points out that many peoples “changed their names over time” and that the Triballi “were once called Dardanians, and are now called so”¹. This passage is essential, because it shows that the name “Triballi” did not represent a permanent identity, but a label that was applied to a population in a certain historical period.

In the same vein, the sources mention the disappearance of the Triballi as a name, but not as a population. They are described as weakened after internal conflicts and pressure from neighbors, especially from the Scordisci, but there is no mention of biological extermination. This shows that we are dealing with a terminological, not ethnic, extinction.

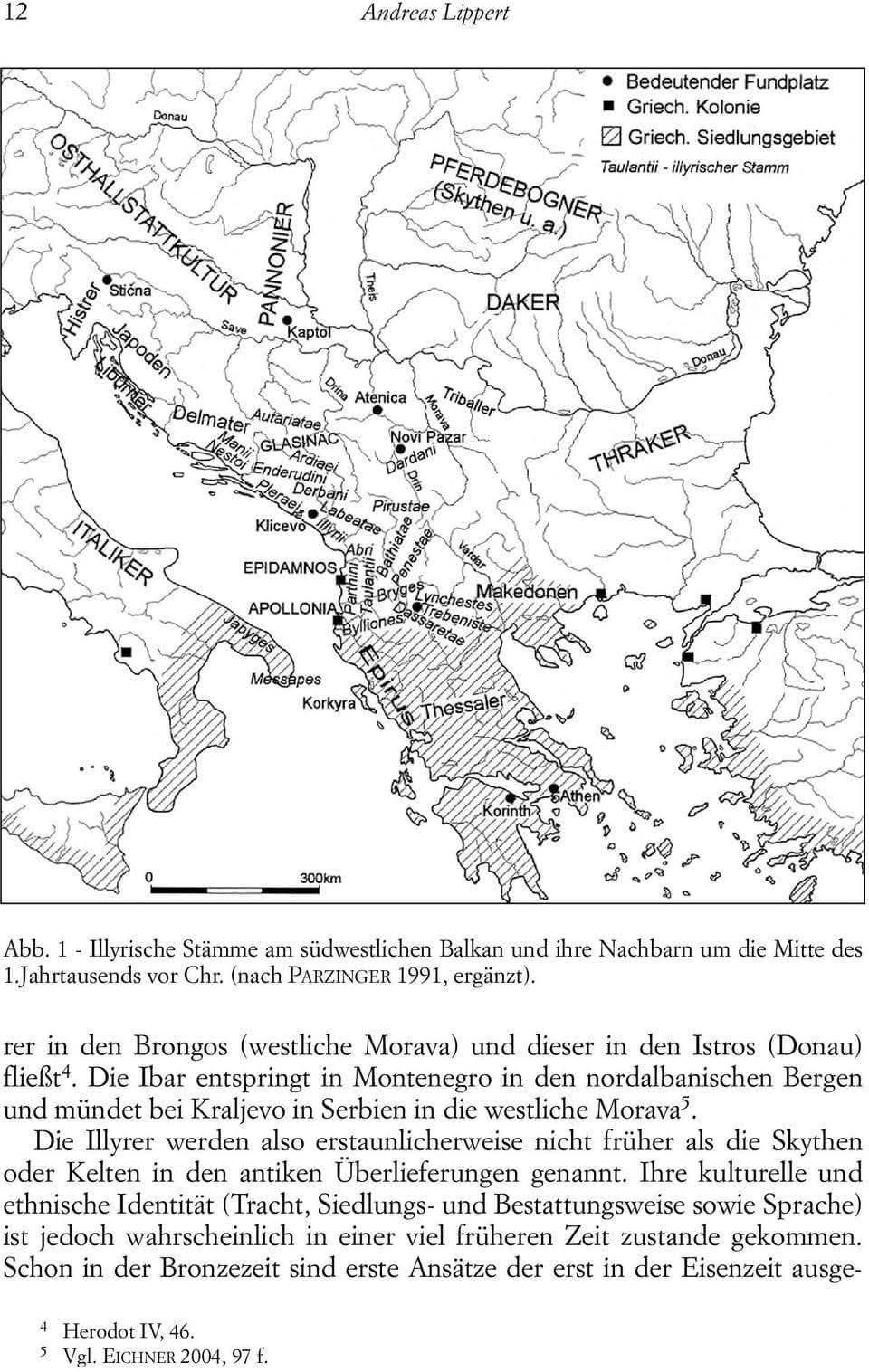

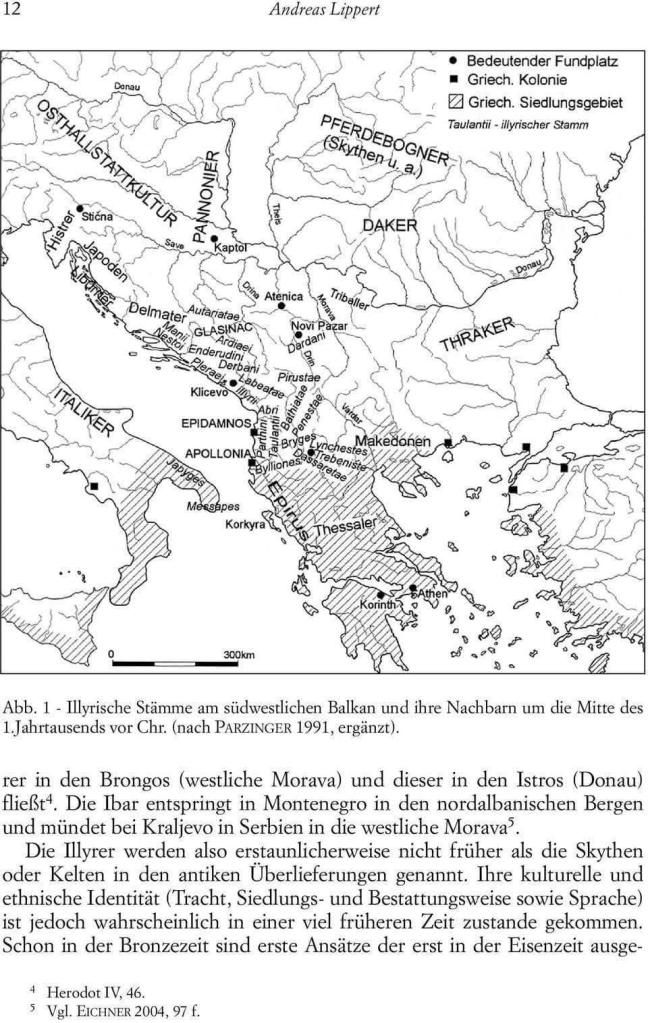

The Triballi and the Scordisci are often mentioned in the same geographical and historical context, especially in the area between the Morava, the Danube and the central Balkans. The Scordisci, although often referred to as Celts, in reality represented an Illyrian-Celtic confederation, which was quickly Illyrianized in the Balkans.

The constant conflicts between the Triballi and the Scordisci, mentioned by ancient authors, do not testify to different ethnic affiliations, but to tribal rivalries within the same Balkan cultural space.

Furthermore, the social organization, the way of fighting and the territorial settlement of the Triballi correspond more to the Illyrian model than to the Thracian or Dacian one. This makes the thesis that the Triballi belonged to the inner Illyrian world, just like the Scordisci, despite external influences, more stable.

One of the main sources of confusion is the use of the terms “Getae” and “Dacians” by different authors. Dio Cassius states that he calls them Dacians, as the Romans do, although some Greeks call them Getae. ³ This statement is not an ethnic statement, but a terminological clarification. For the Romans, “Dacians” was an administrative and military term, while for the Greeks “Getae” served as a general designation for the populations beyond the Ister.

The Triballi, who at one time were displaced or pushed northward, were included in this broad category of designations. This does not mean that they were ethnically transformed into Dacians, but that they were perceived as such by Roman authors, in function of the political realities of the time.

Modern historiography, especially that of the 19th and 20th centuries, has often treated ancient sources in an anachronistic manner, projecting modern concepts of ethnicity and nation onto ancient realities. In this context, the Triballi have been artificially “Thracized” or “Dacianized”, often to support later national narratives. These approaches ignore the fact that ethnic names in antiquity were mobile and dependent on the author’s perspective.

A critical analysis of the sources shows that the classification of the Triballi as Illyrians is more geographically coherent, archaeologically more consistent, and less contradictory than other alternatives. They represent an Illyrian population with strong contacts with the Thracian and Dacian world, but not a “pure” ethnicity outside the Illyrian context.

The Triballi should not be seen as an unsolvable ethnic enigma, but as a typical example of the way ancient authors conceived and named populations. They belonged to the central Illyrian space, in the same tradition as the Scordisci, and were renamed according to historical circumstances and the perceptions of the authors.

Distortions, both ancient and modern, stem from a misunderstanding of the fluid nature of identities in antiquity. Therefore, placing the Triballi in the Illyrian context is not an ideological act, but a reasonable and methodologically defensible conclusion.

Footnotes

¹ Strabo, Geographica, VII.

² Appian, Illyrica; see also Strabo, IV–VII on the Scordisci.

³ Dio Cassius, Historia Romana, LXVIII.6.