Abstract

This study examines the anti-Ottoman uprisings of Himara from the fifteenth to the late sixteenth century, focusing on the political, military, and diplomatic connections between the Himariote Albanians and the Spanish monarchy, particularly through Naples. Drawing on archival documents preserved in Spanish repositories, especially the Archivo General de Simancas, and analyzed by the Spanish scholar José Manuel Floristán, the text reconstructs repeated attempts by the inhabitants of Himara to secure Spanish support against Ottoman rule. It highlights the strategic importance of Himara in the Adriatic, the continuity of Albanian resistance, and the limits of Spanish intervention, which favored indirect support, intelligence gathering, and material aid over direct military occupation. Ultimately, the material reveals both the persistence of local anti-Ottoman agency and the constraints imposed by broader Habsburg–Ottoman geopolitics.

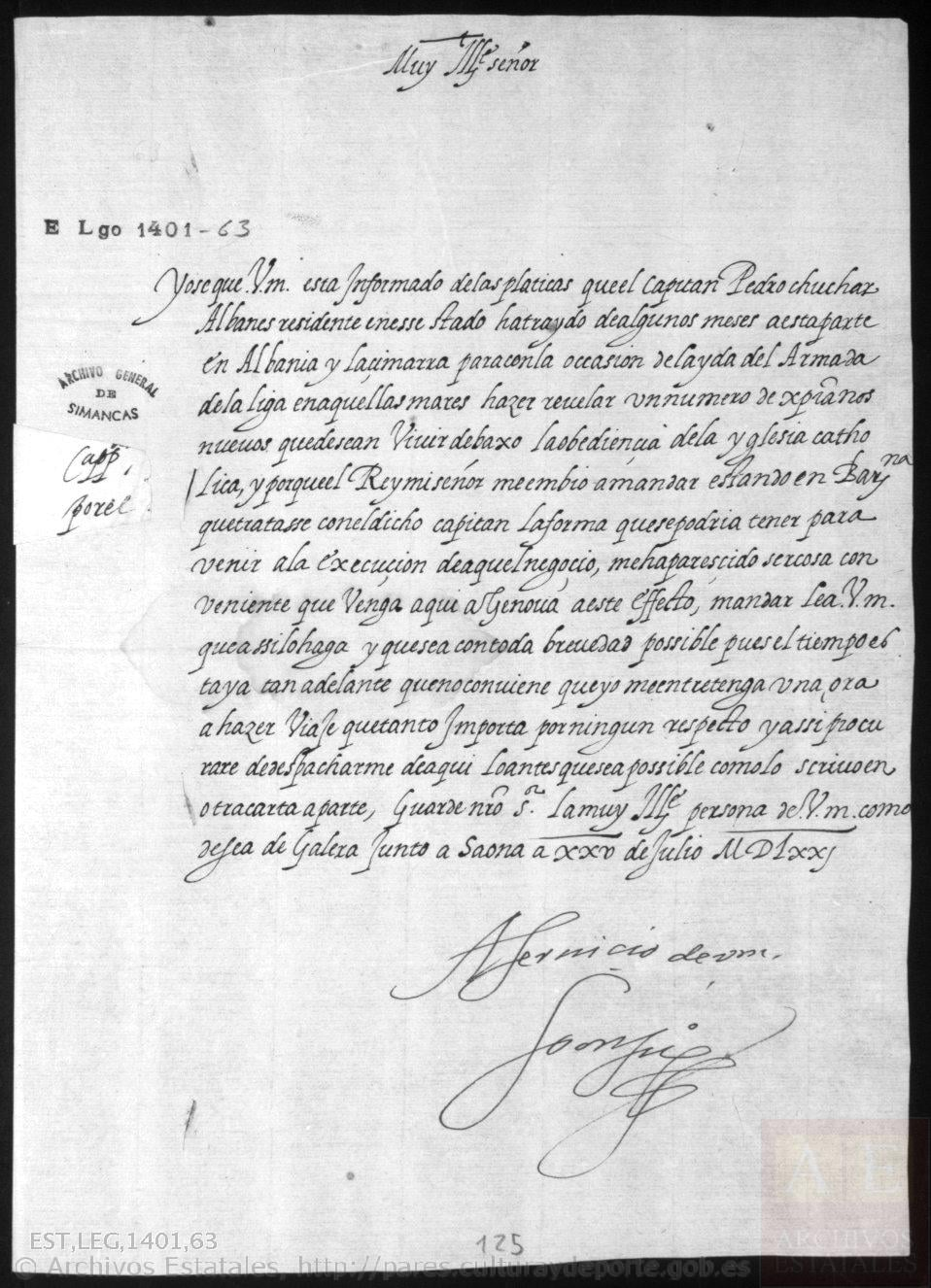

The following archival document (25.7.1571) is entitled:

“Letter from Juan de Austria to Gabriel de la Cueva y Girón, Duke of Alburquerque, Governor of Milan, for the assistance requested by the Catholics of Albania and Himara to rise up against their oppressors: sent by the Albanian captain, Pjetër/Petro Kuça”.

(Letter from John of Austria to Gabriel de la Cueva y Girón, Duke of Alburquerque, Governor of Milan, concerning the request for help from the Catholics of Albania and Cimarra to rise up against their oppressors: commission from the Albanian captain, Pedro Chuchar.)

This document is found in the Spanish general archive (Archivo General de Simancas). Regarding Albanian-Spanish relations and mainly those of the Albanians of Himara, the Spanish researcher Jose Manuel Floristan has written.

The Spanish scholar José Manuel Floristán can rightfully be called one of the discoverers of the history of the Arbëresh of Spain. At the Assembly of Albanology, he presented the history of the archives of the political and social life of the Arbëresh of the 1600s and the relations with the King of Spain, Philip III.

“I, who am mainly concerned with Hellenistic culture, first noticed these documents in the San Marco archive.”

And there I came across all the documentation related to the Albanians of Himara, Naples, and Sicily. So I started to collect them in relation to the themes they had.

Then, data was discovered on stratiotes of Albanian origin who had relations with the Kingdom of Naples.

I have seen in those archives a large documentation pertaining to Himara. The documents cover Himara in general terms with the surrounding areas, Vuno and beyond, and relate to life, history, and all the people in its surroundings.

Himara was on the coastline very close to the kingdom of Naples and the kingdom of Spain supported the Albanian and Naples alternative, because it was against the Ottoman occupation. The ties of the kingdom of Spain with the Arbëresh have been since the time of Skanderbeg,” said Spanish scholar José Manuel Floristán.

For his merits, José Manuel Floristán was accepted as an honorary member of the Albanian Academy of Sciences. (Hamzai, Dh. “Shqiptarja”, December 31, 2021).

Below you will find complete material regarding these relations of the Albanians of Himarj with Naples and Spain.

————————————————————

DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS BETWEEN HIMARA AND THE KINGDOM OF NAPLES

The political and diplomatic relations of the medieval Spanish kingdom with Albania were not intense, for reasons that are easy to understand. The geographical distance, the belonging to two different cultural environments and, in the Spanish case, the focus on the project of the Reconquista of the peninsula, made Spanish-Albanian contacts practically non-existent. With the exception of the transient episode of the conquest of Durrës by the naval fleet of Luis de Évreux in 1376, which quickly left Albania and crossed into the Morea, it was not until the reign of Alfonso V of Aragon (1396-1458) that Spanish-Albanian relations intensified.

By: Jose Manuel Florist Imizcoz

Translated from Spanish: Kebriona Veliaj

As King of Naples from 1442, Alfonso embarked on an ambitious Balkan policy, like his Norman predecessors, the Hohenstaufen and the Angevins. This policy brought him into conflict with Venice, which did not welcome the control of both sides of the Strait of Otranto by the same prince. Alfonso’s intervention in the Balkans was focused on the Adriatic front of Epirus and Albania. He formed alliances with Gjergj Kastriot “Skënderbeg” in central Albania and with his father-in-law Jorge Arianit (Gjergj Arianiti) in the south.

In 1451, he signed a treaty with Kastrioti, by which he (Kastrioti) recognized the historical rights that the kings of Naples had had over Albania, surrendered Kruja and all his possessions, and promised to pay tribute if he respected their privileges.

In the following years, until the death of Skanderbeg in 1468, Alfonso I and then his son Ferrante I (1458-1494) continued to send aid to Gjergj Kastrioti for the war against the Turks.

This, in turn, went to Naples in 1462 with 4,000 men to assist Ferrante during a pro-Anjou revolution of the nobility that had broken out in the kingdom.

Skanderbeg’s arrival allowed Ferrante to lift the siege of Barletta, defeat the French at Troyes (Puglia), and enter Naples victorious.

This military aid provided by Skanderbeg to Ferrante I became a recurring theme in the memorials that Albanians presented to the Spanish authorities, with which they sought to mobilize them to help them in the same way that Skanderbeg had done before.

Without fear of exaggeration, it can be said that these military relations of Alfonso and Ferrante with Skanderbeg were the foundation of the intensive diplomatic contacts that the Spanish and Albanians maintained throughout the 16th century.

Since then, many Albanians served the Monarchy as military agents and informants, not only in Naples, but throughout Italy and in foreign military enterprises in Germany, Flanders, France, etc.

Alfonso V’s diplomatic contacts with Skanderbeg also opened the door to Albanian emigration to southern Italy in modern times.

L Giustiniani distinguishes seven phases in it, of which the first four took place in the 15th-16th centuries: I) the reign of Alfonso V; II) the reign of Ferrante I, when Skanderbeg went to Naples in his defense; III) in 1468, after the death of Gjergj Kastrioti, when his son John took refuge in Puglia; iv) the emigration of the Coronas and Peloponnesians in 1532-1534.

Various documents are known about the process of settling these emigrations in Naples and its main protagonists.

In February 1519, Carlos V signed a patent naming Captain Lázaro Mates and his successors as protectors of the Albanian, Greek, and Slavic nations.

Lazarus had left Albania at the end of the 15th century, to avoid living under Turkish law, and was the head of a stratiote family, who in the 16th century provided great services to Spain, for which they received the governance of various families in Puglia and Basilicata.

Another family that played a crucial role in the settlement of Albanian immigrants was the Kastriota-Granai family, connected to the Kastriota-Skënderbeg line.

In the 1510s, Emperor Charles V granted Alfonso Castriota-Granai the possessions of the Marquis of Atripalda in Campania, appointed him governor of the lands of Bari and Otranto, granted him permission to build and populate three territories, and confirmed him as captain of 500 fast horse.

From his position in Apulia, Alfonso maintained close contacts with Albania and Epirus, especially with Himara, as we will see later. His brother Ferrando received similar privileges: the Dominions of Sant’Angelo, feudal properties, a captaincy of arms, rents, licenses to build houses, etc.

In addition to Mates and Kastriota-Granai we know the names of other Greeks and Albanians who were granted leases, military appointments, privileges and tax exemptions, such as Demetrio and Jorge Capuzzimati, Jorge Basta, Dionisio Critopulo, Juan Mates, Constantino Musaquis, Jorge Sofiano or Miguel Ralis.

With these privileges and appointments, the Spanish authorities sought two objectives: the repopulation of the abandoned houses in the interior and on the coast of Puglia, most exposed to Turkish attacks, and the social and political pacification of the kingdom against the pro-Anjou nobility. There were several factors that led the Balkan population under Turkish rule to seek the military support of Spain.

First of all, there was the geographical proximity of the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily under Spanish sovereignty. In the case of Himara, the frigate of Otranto crossed the 72 km strait (channel) in just one hour without any obstacles. This gave the Himariotes great freedom of movement in their communications with the kingdom of Naples.

A second factor that determined the intensity of contacts was the ideal of the war against Islam that engaged Spanish foreign policy. Compared to other European countries, such as France, England or the Netherlands, which during the 16th century accepted the Ottoman Empire as another actor on the European stage, Spain maintained the war against Turkey as a prominent feature of its foreign policy.

To these two factors we must add the political and military hegemony of Spain in Europe during the 16th century and the apparent economic prosperity due to the arrival of American silver that helped finance foreign military campaigns.

In the legal plan of dynastic rights, we must remember that the kings of united Spain had inherited from those of Aragon the title of Duke of Athens and of Neopaty, and that Andrés Paleólogo, son of the despot Tomás de la Morea and the last grandson of Emperor Constantine XI, had given Ferdinand the Catholic his rights to the throne of Constantinople.

Furthermore, the Spanish authorities recognized the rights that the kings of Naples had had in medieval times in the kingdom of Albania, the Duchy of Durrës, and the Principality of Achaea.

However, none of these titles and rights determined Spanish intervention in the Balkans, nor commercial interests, which were practically non-existent.

During the first decade of the 16th century, Spain continued a process of rapid expansion through North Africa, from Melilla to Tripoli (1497-1511), which placed it in direct contact with the Algeria of the Barbarossa brothers and with the Ottoman Empire.

In the Balkans, with the disappearance of the Hungarian Blockade State after the Battle of Mohács in 1526, the Holy Roman and Ottoman empires came into contact with the Danube.

In 1529, the Ottomans came to Vienna and in the following years made several incursions into the Danube.

Thus was created the scenario of the Habsburg-Ottoman confrontation in the mid-16th century: Habsburg rule in the Iberian and Italian peninsulas and the northern Balkans as far as Croatia and the Hungarian Plain, and the Ottomans in North Africa and most of the Balkan Peninsula.

PART I: THE FIRST REVOLTS OF THE HIMARIOTS IN 1433, SUPPORTED BY GEORGE ARIANITI

In this war scenario, the Himara region played an important role in the fight against the Turks with Spanish support.

In addition to the city that gives it its name, the region includes six other villages, Palasë, Dhërmi, Vuno, Pilur, Kudhës and Qeparo.

Its proximity to Italy made it a suitable place for a possible landing of Christian troops and, conversely, a danger for the Apulian coast to fall into the hands of the Turks.

Its rugged terrain made it easy to defend against internal attacks, but against this advantage was the disadvantage of its agricultural poverty and endemic food shortages, which in the event of the deployment of Spanish forces would make them constantly dependent on supplies from abroad.

In addition to the villages mentioned, there were other neighboring regions of Himara that regularly participated in Spanish-Himariot contacts, such as inner Himara (Labëria) or the coastal villages from Borsh to Saranda.

In 16th century texts, there is usually no distinction between them, but they are all called Himara together.

When the Turks took Ioannina in 1430, almost all of Epirus remained in their hands, except for isolated areas such as Parga, Butrint or Himara.

The first revolts of the Himariotes are already documented from these dates. In 1433 they supported Jorge Arianites (Gjergj Arianiti) and soon after joined Skanderbeg’s war.

In the first Turkish-Venetian war (1463-1479), the stratiotes in the service of Venice captured the fortress of Borsh (Kalaja e Borsh) while the Himariotes conquered other cities.

However, with the peace of 1479, all the conquered territories were returned to Turkey, including the city of Himara. Two years later, Corcodilo Cladás, a Peloponnesian estradiot who had fought against the Turks and who, after the signing of the peace, had entered the service of Ferrante I of Naples, descended on Vlora and conquered fifty cities, among them, again Himara, which was surrendered to Gjon Kastrioti, son of Skanderbeg.

During the Second Turkish-Venetian War (1499-1503), Venice lost almost all of its continental Balkan possessions, including the city of Durrës.

In this way, the Ottoman Empire strengthened its territorial dominance and opened a new phase in which it would transform into a great naval power. Until the end of the 15th century, the inhabitants of Himara had had the naval support of Venice, but when the Turks controlled the coastal cities of the Adriatic and Ionian Sea (Durrës, Vlorë, Lécautë, Lepanto, Coron, Modon), the situation changed radically.

Ottoman pressure gradually increased, being felt especially in the interior areas, which slowly underwent a process of Islamization.

This pressure sought to eliminate the privileges initially granted and to introduce into Himara the fundamental institutions of the Ottoman Empire’s domination, such as the capital tax imposed on non-Muslims (haraç), the conscription of Christian children for the sultan’s central armies (devşirme/janissaries), and the system of distributing land into parts (timars) that were designated for the feudal cavalry (spahi).

In 1518, the first vizier Ajaz Pasha, a native of the village of Palasë, in exchange for a series of privileges, including exemption from capital taxation, administrative and judicial independence, and military autonomy, forced the Himariots to surrender to the Sublime Porte.

They only had to pay a small annual tax in recognition of the sultan’s sovereignty and contribute a regiment to the Porte’s expeditions. In these new circumstances, the Himariotes went to seek help from the Spanish of Naples.

Thus began relations that would last, with ups and downs, for almost two centuries. There are three most frequent periods of contact in the 16th century and the first decades of the 17th century, coinciding with other periods of the Ottoman Empire’s war peaks: the 1530s with the war against the Emperor on the Danube; the years around Lepanto, from the failed Ottoman attempt against Malta (1565) to a few years after Lepanto, and the last years of the century and the beginning of the following century, coinciding with the war against the Emperor on the Danube (1593-1606) and against Shah Abbas of Persia (1602-1614).

PART II: THE 1530S, DOCUMENTATION OF HIMARA’S FIRST CONTACTS WITH NAPLES

The first documented contact of Himara with Naples is a letter in March 1530. In it, three priests and gentlemen of the area testified that there was no plague and therefore Captain Demetrio and his sailors, who had been sent by Lord (micer-title) Cristoforo to load oak, were not carriers.

In the second part of the letter, the Himariotes declared themselves vassals of Emperor Charles V and requested a letter from the authorities in Naples to confirm this vassalage. When he arrived in Otranto, Demetrio approached the first man he met and told him that they wanted to be vassals of the emperor.

Fernando de Alarcón, general of the kingdom of Apulia, and Alfonso Kastriota-Granai, governor of the Land of Bari and Otranto, sent to Himara an agent named Andrés de Otranto, who returned on April 27 in the company of six leaders from the region, who requested one thousand ducats for fortifications, five hundred arquebuses (firearms), food, and a government person.

Alarcon gave them part of what they had requested, ordered them to monitor the movements of the Turks, and gave them a frigate to send news.

This first contact already shows two characteristics that would be maintained later, the fluidity and speed of communication between the two sides of the channel and the divergence of interests of the Himariotes and the Spaniards: while they sought military assistance for an anti-Turkish revolt, the Spaniards sought the creation of an information and espionage network.

In letters to the emperor and Pompeo Colonna, the vicar of Naples (1530-1532), Alarcon was willing to fortify a place so close to Naples in Ottoman territory. This was the year after the first Turkish attack on Vienna (1529) and two years before the capture of Cortona (1532) by Andrea Doria, so the possibility of a military invasion of the region could not be ruled out.

However, from the beginning, the policy of limited support that the Spanish authorities preferred is evident: weapons and ammunition, food and materials for fortification and, occasionally, one or more captains to direct operations, but never any assistance with troops or a military occupation of the country.

The Himariote embassy had consequences. In August of that year, Atripalda communicated to the emperor that the Sanjak of Vlora had ordered the killing of the mayors of Himara, who had surrendered as vassals to the Spanish authorities. Like Alarcon, Atripalda thought that mastery of the region could be achieved with little expense and great benefits.

In April 1531, three more ambassadors from Himara arrived in Puglia and reported on their victories in their clashes with the Turks. It seems that there was a great upheaval in Albania that year, also from other northern tribes.

At that time Atripalda sent two of his men to Constantinople, Juan Zagorites and Dopno Apolonio, who on their return informed about the preparations of the Turks to attack the Portuguese from the Red Sea. In July, the Himariotes repeated in a letter their submission to the emperor and asked for help.

From the letter we know that the Venetians had taken away the ship with which he had taken back from the six ambassadors of the previous year the protector Dimo Prono. This action, like others that we will see, shows the opposition of Venice to the contacts of the Balkan peoples in general, and of the Himariotes in particular, with the Spanish of Italy.

The reason for this opposition was the fear that the insurgent movements could disturb the fragile peace they maintained with the Ottoman Empire. A letter from Atripalda to the emperor gives us more news about the information brought by the ambassadors.

According to them, the region had 70-80 rebellious villages from which 20,000 soldiers and 2,000 cavalry could be recruited. In another letter of November 1531, Alarcón again appeared in favor of meeting the demands of the Himariotes, because with a small expense a great profit would be obtained.

The year 1532 was rich in news and military events. That year, a new Ottoman expedition reached Köszeg (Güns) on the Danube and the imperial army occupied the squares of Corona and Patras in the Peloponnese.

The unrest experienced in Himara in previous years reached its peak that year with the determined support given to the emperor’s armies. On May 9, the Himariotes wrote a letter to Alarcon, informing him of the preparations of the Ottoman army in Sofia and Ipsala and the objectives of the Turkish army.

Before the unrest that the region was experiencing, the Sanjak of Vlora sent an order to the priests and elders of the cities of Vuno and Dhermi informing them of the sultan’s return from the expedition against the Portuguese and the dispatch of the first vizier Ibrahim Pasha to More with a large army to destroy him, because he had heard of the “vain conversations” they were having, alluding to a rebellion related to the external contacts that the inhabitants of the Peloponnese had. Since the Sanjak knew that the inhabitants of Himara also had external contacts, he ordered that Togis Tetusis of Vuno and Count Pitzilis of Dhermi appear before him to clarify the situation. The order was sent to Otranto by the Himariotes, perhaps with another letter of his, to demonstrate the danger that threatened them and to force the sending of Spanish aid.

That summer of 1532, Atripalda decided to send Cristoforo Trombetti to Himara with a letter of his own, asking its inhabitants about the situation in the region and their intentions. He returned with another letter signed by the elders and leaders of the country, headed by his protonotary, dated 14 August.

The letter from the Himariotes reiterated their readiness to serve Spain, reported the shortage of grain, and requested weapons. They provided a list of the lands that make up the province of Himara, divided into four zones: coastal, mountainous, hilly (Duchy area), and the plain of Vlora.

The capture of Corona by Andrea Doria on 22 September 1532 rekindled the hopes of the Himariotes, who gathered a thousand men awaiting a captain and the king’s order to attack Vlora. Atripalda told the vicar of Naples in a letter dated 2 October with news brought by a certain Gjergj Bullari, who had passed through the region.

Shortly after this, four other Himariotes arrived in Lecce, who described to Atripalda their country and the quality of their lands and inhabitants, and asked him to make a decision on their proposals, because the current circumstances were irreparable.

A new letter of 11 November informs us that twelve days after the departure of these four envoys (emissaries) from the region, others wanted to go to Naples in the company of Cristoforo Trombetti, but were prevented by a Venetian galley, which accused them of robbery and began to bombard them. The practice of piracy by the Himariotes is mentioned by several sources of the time.

Judging by the evidence, on occasion they used the weapons sent by the Spanish not in the war against the Turks, but in acts of piracy against Christian ships that passed near their coast. Because of their commercial traffic with the East, the Venetians were most affected by this practice, and from this stemmed their complaints against the Spanish authorities who sent them weapons.

In the November letter, the Himariotes communicated the arrival in Arbëri of several couriers to offer the leaders a good reward if they destroyed Himara. Finally, the Himariotes asked Atripalda to send their four ambassadors home with heavy protection, because the Turks and Venetians were guarding all their movements by sea and land.

At the end of the year, Atripalda sent a letter to the Himariotes to keep them loyal to the Spanish crown. 1533 was the year of the Ottoman reaction. As the governor of Vlora had notified the elders of Vunoi and Dhërmi by his order, Ibrahim Pasha crossed with his army to More.

The news reaching Naples spoke of the destruction of several villages in the Patras-Cálabrita area and of an intensification of Janissary activity, which forced the inhabitants of the area to seek refuge in the mountains and await the counterattack of the imperial army there. The same situation was experienced in Vlorë and Himara.

From a letter of September 6 and from information from several envoys in Puglia, we know that when Andrea Doria’s army left Coroni, where it had brought supplies and aid, four sanjaks had gone to Vlora to protect the city from a possible landing of the imperial fleet.

After this was finally not achieved, the Sandzaks took advantage of the meeting to attack Himara. One of them attacked Butrint and killed 30 young men, but suffered many casualties in his own ranks. After the attack, representatives from all the houses of the region met again and decided to send new ambassadors with a letter to ask for help from the Spanish authorities.

This is all that is known about this first phase of Hispano-Himariot contacts. The lack of archival documentation since September 1533 indicates a sudden suspension.

The reasons for the interruption are easily understood: a) In the spring of 1534 Carlos V repatriated the garrison of Coroni and brought to Naples both the Greeks and Albanians who wanted to leave the city. The difficulty of supplying the square and the high economic cost of its defense brought about this withdrawal.

b) In 1533, Jairedin Barbarossa, Lord of Algiers, surrendered to Suleiman, who appointed him Admiral of the Ottoman fleet and Beylerbey of North Africa, and in February 1536 Suleiman signed a treaty of friendship with France. With these two historical facts, the Spanish-Turkish confrontation shifted from the central Mediterranean to western and northern Africa (the emperor’s campaigns against Tunisia in 1535 and Algiers in 1541).

In 1537, the sultan planned a landing in Apulia and, taking advantage of his stay in Vlora, attacked the Himariotes, who again sought refuge in the mountains. He then attacked Corfu, starting the Third Turko-Venetian War (1537–1540).

We have some indirect news about the participation of the Himariotes in this war, but the Spanish archives have not preserved any relevant documents of this phase. To summarize, the first phase of Spanish-Himariote contacts took place within the framework of the imperial policy of Carlos V and had as its objective the Spanish side to gather information on the Ottoman advance through the Danube and to distract the emperor from it.

PART III: THE RESTORATION OF HIMARA’S CONTACTS WITH SPAIN THREE DECADES LATER: THE NAVAL BATTLE OF LEPANTO (1566-1577)

It took three decades for contacts between the inhabitants of Himara and the Spanish authorities in Naples to be reactivated. The years between 1560 and 1574 were the height of the Spanish-Turkish confrontation. During these fifteen years, expeditions took place, the Spanish against Djerba in 1560 and the Turkish against Malta in 1565, the naval battle of Lepanto and the epilogue of the conquest and defeat of Tunisia by the Spanish in 1573-74.

Of course, Himara did not stay away from the confrontation. From the documents of this period we know that after the signing of the Turkish-Venetian peace of 1540, the Himariotes were forced to accept the status quo that emerged from it. After it, the Turks took advantage of the relative calm to consolidate their rule in the area.

In 1548 they conquered the territory with good words, imposing a Spanish himariot for the supervision work, which they themselves did, but apparently without imposing tribute or devşirme.

Perhaps at that time the fortress of Borsh, the target of Himariot attacks in the new period of the war, was rebuilt. Later, the Turks assigned them a garrison of 2,000 men to keep them in their territory and finally in 1563-64 they replaced the Spaniards of the fortresses, imposed taxes and tried to introduce the nizam (devsirme).

The patience of the Himariotes had run out, and they once again decided to take up arms. Contacts resumed in 1566, a year after the Ottoman attack on Malta. Two trips by Cristoforo Trombetti to Himara in July and August were used to gain information on the movements of the Ottoman army, which entered the Adriatic Sea that year to support the sultan’s land expedition to the Danube.

The Turks landed in Himara twice, the first time to help the governor of the region to force his inhabitants to pay tribute, and the second time, to punish those who took up arms. According to the news reaching Naples, the uprising was general in the region and only the fortress of Borsh, with 200 men, was in Turkish hands.

To obtain it, the Himariotes asked the Duke of Alcala, Vicar of Naples (1559-1571), for gunpowder and artillery. In early September, Alcalá sent Captain Juan Tomás Saeta with 12 barrels of gunpowder and his letters, which filled the Himariotes with joy.

Saeta spent 18 days in Himara and returned with documents of great interest on the region and its inhabitants: i) the oath of the inhabitants of the city of Himara and other neighbors, such as Kudhësi, Piluri, Zhulati, etc., up to nine (cities/villages) in total, in which they pledged to take up arms against the Turks when ordered to do so by the vicar; ii) a letter from the Himariotes to him; iii) a list of houses and men fit for war of various villages in the region, and iv) a detailed description of the surroundings of Himara.

The one in charge of traveling to Naples with Saeta was Gjin Alexi Zacna, who on behalf of his compatriots requested gunpowder, ammunition, artillery, and several captains to take the fortress of Borsh. In the following years we find several members of the Zacna family involved in Hispano-Himariot contacts: Nicolás, the son of Gjin Alexi, and the brothers Stratis and Gjin, probably Nicolás’ children.

The latter mentions a memorial of his from 1616 (see below) to a grandfather named Aleksandër Zacna, perhaps the father of Gjin Alex. According to Saeta’s information, the Himariots were brave men, of good stature and strong, and were armed with short swords, and some with long swords. There was a shortage of arquebuses (a type of rifle) in the region, so they requested that a thousand of them be sent to them.

The area controlled by the Himariotes was 60 miles long and had very few Turks. To keep them loyal to the Spanish crown, Saeta recommended that salaries be paid to the leaders of the region. He also reported that the fortress of Borsh, located eight miles from Himara and one mile from the coast, had a wall four palms wide and a garrison of 150 men (with women and children, a total of 1,000 people).

The vicar gave Gjin Alexi food and asked the court in Madrid what to do with the request for weapons. In revenge for the defeat inflicted on Admiral Pialí Bajá in 1566, in the summer of 1567, the new sultan, Selim II, sent seven sanjaks against Himara to punish its inhabitants.

We have not kept documents from the following years, but from indirect news we know that contacts between Himara and Naples were not interrupted. However, Spanish aid never materialized in the sending of an army, which was the request made by the Himariotes, so in 1570 they decided to go to Venice, from which they received a quick response.

PART IV: ON LOYALTY TO THE KING OF SPAIN…

In May, the elders of the towns of Himara, Vuno, Dukat, Pilur, Dhërmi, Palasë and Ilias pledged allegiance to Venice. The general sea supplier Sebastiano Venier went to Himara and on June 10 took the fortress of Borsh. After the success, other villages joined the rebels.

At the same time, Pedro Chucharo, an Albanian stagehand in the service of the Spanish in Milan, made a proposal for the uprising of some mountain tribes of Albania and Himara, who, according to his information, wanted to rebel. According to Chucharo, the Albanians preferred to fight on the side of the Spanish because of the arbitrariness that the Venetian fleet was carrying out in their territory.

The capture of Borsh had shown that the Albanians’ readiness was sincere and that the possibilities of conquest were real, but Spanish policy in the area did not foresee open military intervention. The enterprises of Coron (1532-34) and Herceg Novi (1538-39) in the time of Carlos V had shown that a surprise invasion was possible, but that holding conquered territories was difficult and costly with an enemy rear.

The Spanish authorities encouraged and supported the revolts of Christian communities dissatisfied with Ottoman policy as a means of weakening Turkey, but not of incorporating their territories into the Monarchy. Venice, on the other hand, supported the military proposals that came to it in times of war, but when it signed peace with Turkey, it quickly returned to the occupied territories and did not hesitate to suppress any attempt at revolt that might break it.

The signing of the Turkish-Venetian peace of 1573 was a disappointment for the Himariotes, who again sought the Spanish alliance. In August of that year, a Himariote named “Gincha” arrived in Otranto to meet Juan de Austria. In the letter he brought, very short, the Himariotes expressed their devotion to Felipe II and Don Juan and their desire to fight and die under their flag.

In the following years, Spanish-Himara diplomatic contacts were reactivated once again. In July 1575, Juan Andrea Segna (or Tegna) presented a report on Himara, where he had traveled. In it, he claimed that the situation of its inhabitants was desperate, because a joint attack by sea and land by a large contingent of Turks was expected, which later news dimmed (the number of Turks). As it was said, their objective was the fortress of Borsh, which was apparently in the hands of the rebels.

In addition to its direct contacts with the Spanish authorities in Naples, Himara was also involved during the 16th century in the anti-Ottoman activities of the two archbishops of Acrid (Ohrid), Joaquin and Atanasio I.

In 1573, two Epirote nobles, Mateo Papajuan and Pano Cestólico, proposed on behalf of Joaquín de Acrida to Juan of Austria the organization of an uprising in “Lower Greece,” that is, in Northern Epirus and western Macedonia. In May 1574, Papajuan presented several memorials in Madrid, in which the ease with which the provinces of Lower Greece and Albania could be conquered was highlighted.

From Madrid Papajuan was sent to Sicily to meet with Juan of Austria, who responded to the bishops and leaders of the region with a letter dated 9 October 1574 in Trapani in which he expressed his satisfaction with their desire to fight against the Turks and assured them that the misfortunes suffered by his army that summer (the losses of Tunis and La Goleta) would not prevent him from coming to their aid.

He therefore asked them to send him a detailed report of their forces, the supplies they needed, the Turkish troops in the area, the possibility of holding the invasions, etc.

On June 24, 1575, he handed over a guide to Captain Antonio de Echávarri, who had been ordered to travel to the area to explore it, with instructions on what he should do during the journey. Echávarri was to get to know the entire region and collect data on natural paths, strong and weak places, Turkish fortresses, the natives, the weapons they had, the possibility of using cavalry, etc.

He had to pay special attention to the squares of Vlora and Borsh, from which Turkish aid could be launched. In addition to Mateo Papajuan and Gjin Alexi Zacna, in the company of Echávarri, his sons Nicolás and Andrés Musaqui (Ndreu Myzaqi) also traveled. The one responsible for taking them to Himara on his frigate was Juan Andrea Segna, who had just returned from Himara and had presented the aforementioned alarming report.

However, the mission continued forward and on 13 July the delegation entered Otranto on its way to Epirus. The journey lasted a little over a month. The report written by Echávarri on his return is dated 19 August. In it he addressed all the points he had been ordered to investigate.

He says that the region is harsh and strong, difficult to penetrate from the coast. Their only weak point was the location of the fields on the coastal plateau, which made them vulnerable to the sea. He describes its inhabitants as warlike, fierce enemies of the Turks and very devoted to the crown of Spain.

The most respected man among them was Gjin Alexi Zacna, although his advanced age prevented him from starting the enterprise and governing the Himariotes. Echávarri says in his report that the territory produces the main foods for their livelihood, but they are not in the habit of storing them from one year to the next, but sell the surplus.

There is only one large river in the region, the Vjosa, which does not pose an obstacle to the enterprise, because it is beyond the mountains. On the other side of the river is the land of Albania in the direction of Durrës, where more than 100,000 warriors could be gathered. In Echávarr’s opinion, if Vlora and Borsh were conquered, the inhabitants of Himara could wage war on the Turks without great difficulty, because the Turks could not attack them from the sea with these places in their hands.

Thus, once expelled from Albania, the Turks could no longer return from any of its three entrances, neither from the north, nor from the east, nor from the south. If the Turks had taken it after the death of Skanderbeg in 1468, it would have been due to the internal discord of its inhabitants, but now they had learned their lesson and were ready to die before they would let them enter their territory again.

Echávarri was in favor of removing the Turks from Borsh and postponing the undertaking at Vlora until later. In his opinion, with a hundred galleys (ships or garrisons), all of Lower Greece could be conquered, from Durrës to Ioannina and the three passes mentioned.

On August 31, Don Juan de Austria was ordered to send the Himariots the requested help with gunpowder, ammunition and a thousand arquebuses, because they were not in danger. The later news is somewhat confusing. Those of 1575 speak of the defense of the Borsh fortress by the Himariots and those of 1576, of its reconquest, because apparently the Turks had recaptured it in the autumn-winter of 1575-76.

After the reconquest, the Himariots asked the Marquis de Mondéjar, the Vicar of Naples (1575-1579), whether they should hold the fortress or destroy it. Mondéjar chose the latter option and entrusted it to the Greek agent Pedro Lantzas. Lantzas arrived in Himara on 29 July 1576.

After taking the inhabitants’ oath of loyalty to the King of Spain, he went with them to the fortress of Borsh, which they dismantled (July 29-30). Three months later, on November 2, a new letter from the Himariotes tells how they had submitted years earlier to the Duke of Alcalá and how they had fought against the Turks, especially on the day of Lepanto.

Despite this, Spanish aid had not gone beyond promises, except for the weapons brought by John of Austria and the dispatch of Lantzas to dismantle Borsh. After this success, the Himariotes proposed to the Spanish the capture of Vlora, which could be done with 20 galleys and 3,000 soldiers, while they took (captured) the mountain passes.

They also requested permission to receive supplies from Naples, because the Venetians of Corfu, their usual place of supply, had embargoed them for their war against the Turks. The Vicar Mondéjar was against the Vlora venture because of the danger and little benefit, but permission was granted to receive one hundred cartloads of grain from the kingdom.

The last action we know of the embassy of Lower Greece is the letter of June 1, 1576 that Joaquín de Acrida sent to Juan de Austria in response to his letter of October 9, 1574. In it, he expressed the joy he had felt upon receiving his letter, but also the sadness that the rupture of the Holy League had caused him and, above all, the indifference of Juan de Austria, because if he had acted earlier, great victories would have been achieved due to the weakness of the Turks.

Joaquin requested the sending of an agent to his territory for greater credibility of his proposals. From 1577 there is a new request for arms, ammunition and food for the Himariotes presented in Madrid by the Albanian captain Pedro Luche. Felipe II sent him to the Vicar of Naples, to whom he gave permission to send arms and ammunition to the region, but not direct help with fighters.

From 1577 onwards, news about Himara ceased once again. The reasons for this are obvious: first, the armistice signed by Spain and Turkey in February 1578, which made it unthinkable for the Sublime Porte to simultaneously support the rebels; second, the Atlantic “turn” of Spanish foreign policy after the start of the open war of Flanders (1572) and the inclusion of Portugal in the Monarchy (1580), which diverted Philip II’s attention from the Mediterranean; third, Spain’s increasing attention to American affairs; and finally, the disappointment and fatigue of the Himariotes after a long decade (1566-1577) of unanswered requests.

It was necessary to wait for the arrival of a new generation so that the Himariotes could once again seek Spanish help. This silence of the Spanish archives after 1577 contrasts with the abundance of evidence about diplomatic contacts established with Rome between 1577 and 1582. The Himariotes sent at least four embassies to Pope Gregory XIII and several cardinals, for which we have preserved some original documents.

In their letters, the Himariotes requested financial assistance to rebuild their church and the Pope’s intercession to Philip II of Spain to send them military aid. These embassies have been well reconstructed by other scholars before me, so I will speak of them so as not to affect relations with Spain (I do not understand what the author meant by this).

PART V: THE REVOLT OF ATHANASIOS OF ACRIDA (OHRI)

Forced by plague and famine, the Himariotes submitted to the Turks in 1590. The Dutch traveler Jan van Cootëijk (Cotovicus), who passed through the region a few years later, states in his travelogue that the Venetians had forbidden the inhabitants of Corfu to receive any Himariotes for fear of catching the plague and that they had denied them the right to buy food on the island.

This forced the Chimarrots to surrender to the Sanjak of Epirus, with whom they signed a pact. However, the calm did not last long. The outbreak of the war between Turkey and the Empire on the Danube side (1593-1606) revived the desire for rebellion against Ottoman rule.

In the summer of 1594, two envoys from Himara arrived in Rome to request arms, ammunition and gunpowder for the war against the Turks. In October, the Pope sent its inhabitants a letter, in which he advised them to remain faithful to the faith (religion), and some arms and ammunition. But the real protagonist of the contacts between Himara and Naples in the last years of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century was again an archbishop of Acrida (Ohrid), Athanasius I.

In a memorial he presented in 1598 at the court of Emperor Rodolfo II (1576-1612), Athanasius recounted how he had placed himself at the head of the Himariote revolt. In the summer of 1595 the ecclesiastical authorities of the province of Acrida (Ohrid) held a synod in which they decided to organize a Sicilian vespers and to send a messenger to the princes of Christendom to ask for help.

The chosen ambassador was Athanasius himself, who, under the pretext of a pastoral visit to the region of Dropulli, went to Himara with the intention of going to Naples. Athanasius was recognized by its inhabitants, who took him in and put him at the head of the rebellion in which they were immersed.

Venetian sources claim that Athanasius first came into contact with the Venetians of Corfu. The general sea-provider Antonio Basadonna traveled to Butrint, where he met him on 26 January 1596. Athanasius assured him that the Spanish were trying to stir up Albania in revolt and that they had sent letters to various lords of the region to this effect.

He also told him that they had sent arms and ammunition to the Himariotes. Finally, he offered to give the Venetians all of Albania south of Durrës. The offer was rejected by Basadonna, so Athanasius decided to contact the Spanish in Naples.

From the dispatches of Giovanni Sagredo, the bailiff (old term baili) of Corfu, we know that, after the embassy of the Himariotes to Rome in 1594, the frigate of Otranto had taken up arms in Himara with papal permission, arms that, according to Sagredo, its inhabitants had not used against the Turks, but in acts of piracy against Christian ships passing along its coast.

He also accused them of doing business by reselling to the Turks. Sagredo tried to prevent this trade, which provoked the protest of the Vicar of Naples to Girolamo Rannusio, the Venetian ambassador to the kingdom, because the aid to the Himariotes had always been done with the knowledge and permission of the Venetian authorities.

In the summer of 1596, major military and naval preparations were made in Naples, about which Rannusio informed the lord (prince). According to his news, the Spaniards were preparing to conquer Vlora at the proposal of Athanasius, who had promised to raise six thousand Albanians and had requested arms, ammunition and fighters to march against Kanina. Rannusio speaks of 16 companies of infantry, each of more than 250 men, making a total of more than 4000 fighters. Pedro de Toledo, general of the Neapolitan galleys, was ready to cross into Albania, but at the last moment Admiral Juan Andrea Doria prevented him from taking to sea. Juan Andrea, who had fought at Lepanto in 1571 and a year later had gone to Morea with weapons and ammunition to distribute among the rebels without anyone coming out to take them, was skeptical of the proposals for rebellion coming from the east.

It is not surprising that four years later, in 1600, the ambassadors of Dionisio de Larisa, who traveled to Madrid to seek help for their revolt, expressly requested that the command not be entrusted to Juan Andreas, whom they accused of insensitivity and passivity.

Although the Spanish navy had not crossed the channel, as the Himariotes did, several Greek and Albanian captains who were in the service of the crown in Naples did, such as Miguel Bua and Giovanni Golemi, who under the command of the field master Ottaviano di Loffredo took a thousand arquebuses, bullets, gunpowder and fuses.

On 10 August, the Himariotes captured the castle of “La Cerna” (Canina?) under the command of Loffredo, in which a standard-bearer managed to plant the flag. Part of the attackers devoted themselves to plundering and fled to the mountains with the loot. Ottaviano had to hold the occupation with about 50 men, but in the end he was forced to retreat without destroying the castle.

We know the names of other Greeks and Albanians involved in this war effort, such as Esteban Bublia, a native of Corfu, who had participated with Gjin Alexi Zacna in a failed uprising in 1587, or Nikodemus Kostandin, a noble Greek knight and archdeacon of the cathedral church of Acrida (Ohrid).

Judging from the sources, the Himara enterprise, proposed by Athanasius of Acrida (Ohrid), was involved in personal disputes between two agents in the service of Spain in Naples, the Corfutian Pedro Lantzas and the Epirote Jerónimo Combis, general supervisor of the espionage and intelligence service in the Kingdom of Naples.

The former was one of the main supporters of the Himariotes before the Vicar of Naples, while the latter was opposed to his proposals. In the aforementioned memorial of 1598, Atanasio blamed Combis for refusing Juan Andrea Doria permission to go to Himara to the Spanish army in the summer of 1596.

Athanasius accused him of being a double agent in the service of Venice and the Sublime Porte, to which he sent news through a renegade brother. He had been the one who should have convinced Pedro de Toledo not to go to sea, telling him that the rebels of Himara had signed peace with the Turks.

Finally, he should have convinced Búa and Golemi to write a negative report on the situation in the region on their return from Himara, in which they said that the rebels no longer had any strength and that the Turks surrounding them could attack them at any time.

The report contradicted (contradicted) the news brought by a nephew of Athanasius and two Himariote ambassadors, who refuted the version of Búa and Golemi and emphasized the ease of the undertaking. The ambassadors were warmly welcomed in Lecce by Ottaviano di Loffredo, who thus wanted everyone to know that that summer he had been their captain-general in the capture of “La Cerna” (Kanina?).

As on other occasions, the ambassadors received some arms and ammunition, but no aid in men or galleys, so they returned home disappointed. The situation remained unchanged in the following months. The Himariotes asked the army to cross the Channel to support them, but the Spanish refused to help with men and ships.

In the first months of 1597, the inhabitants of the villages and hills of Himara gathered in the presence of Athanasius to show him their obedience. The Turks, on the other hand, were afraid of a possible Spanish attack. At the end of May 1597, two new ambassadors arrived in Naples to ask for more arms and ammunition, but were not received by the vicar.

Faced with the repeated refusal of the Spanish authorities to send the requested aid, Athanasius decided to cross over to Italy. He first traveled to Rome, where he requested four thousand infantry, 20 captains, weapons and gunpowder. The money to pay for these troops would come from the rebels themselves, who had hidden half a million ducats. According to the proposed plan, in early March 1598, the rebels would appear in Vlora and then cross over to Himara, where they would await the forces sent by the Pope.

Athanasius promised to gather 200,000 men to march on Constantinople. After three months in Rome, in January 1598, Athanasius traveled to Naples, where he spent six months. At the end of June, he went to Central Europe accompanied by Jeremiah Bateo, Bishop of Pelagonia-Perleapos (Macedonia). At the court of the emperor in Prague he presented the memorial I have mentioned with information about his life and activities and accused the Venetians as allies of Turkey and enemies of Christianity because they had suppressed the general uprising of Albania and Greece. The emperor gave him some money and a letter of recommendation to the King of Spain.

Source

Rilindasi/shqiptarja.com/