Image from Wikipedia.

Abstract

This article critically examines the ideological glorification of Gavrilo Princip among Serbian chauvinist narratives and situates it within a broader historical pattern of irredentist nationalism in the Balkans. It argues that the celebration of the 1914 Sarajevo assassination reflects a dangerous political mythology that minimizes the killing of civilians and the catastrophic global consequences that followed. The study compares this symbolic politics with Serbian nationalist mobilization during the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. Drawing on historical and political-science sources, the article contends that chauvinist narratives repeatedly framed violence as defensive or liberatory while producing devastating humanitarian outcomes.

Introduction

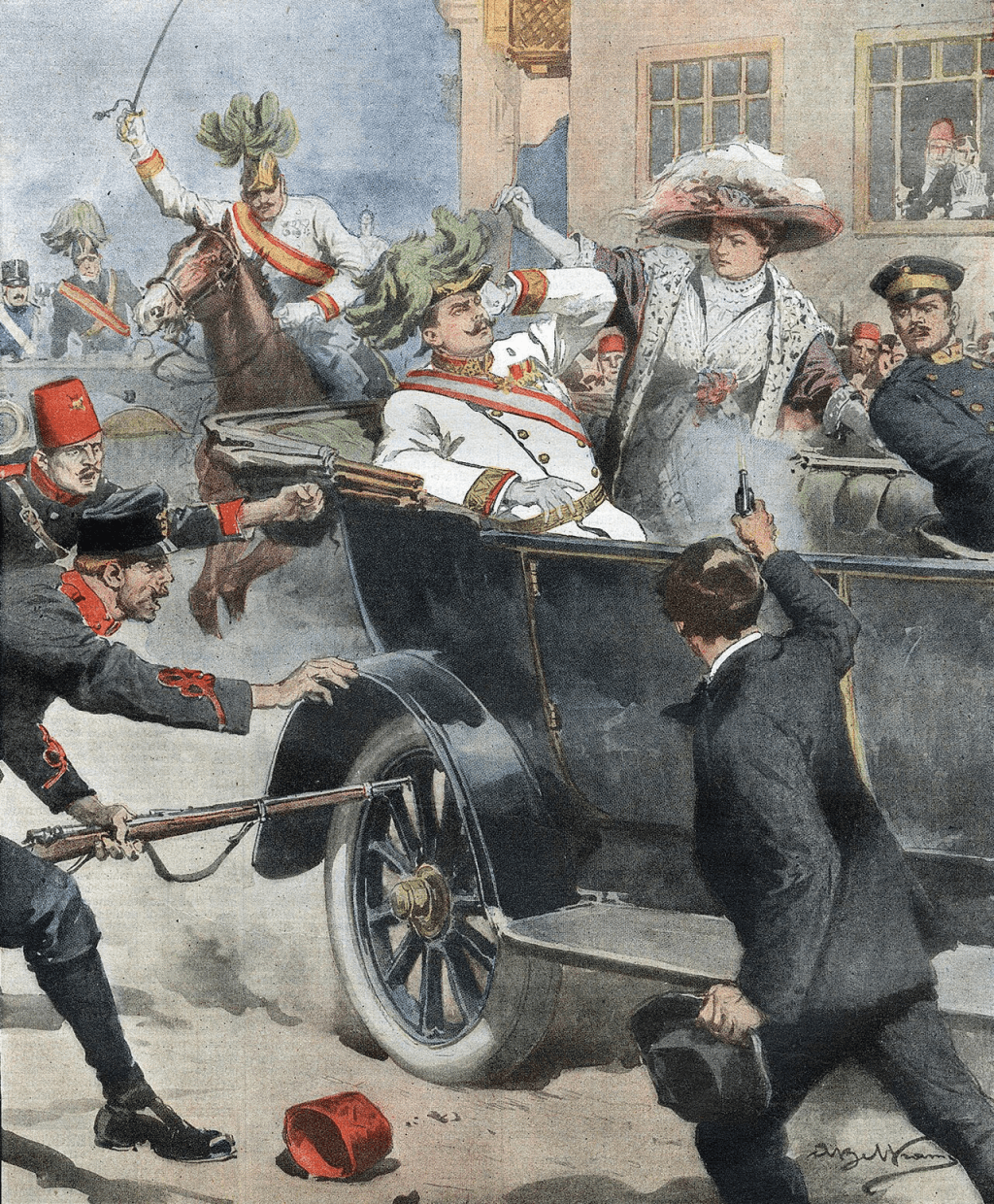

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 was a political murder carried out by a South Slav nationalist, Gavrilo Princip, who had been trained and assisted by networks linked to Serbian secret societies.

The event triggered a chain reaction that culminated in the First World War—one of the deadliest conflicts in human history.

Yet, more than a century later, segments of Serbian nationalist and chauvinist discourse continue to celebrate Princip as a hero. This phenomenon raises profound moral and historical questions. How does the glorification of an assassin coexist with the memory of the tens of millions who died in the war that followed? And why does this narrative resemble later Serbian nationalist rhetoric that contributed to the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s?

This article argues that the celebration of Princip reflects a recurring ideological pattern: a chauvinist political culture that romanticizes violence as a tool of national liberation, even when such violence kills civilians and unleashes catastrophic wars.

The Sarajevo Assassination: Terrorism and Civilian Death

Gavrilo Princip was not a random gunman. He was part of a nationalist network linked to the Black Hand, a Serbian secret society that aimed to destroy Austro-Hungarian rule and unite South Slavs into a single state.

On the day of the assassination, another conspirator first threw a bomb that wounded others; later, Princip shot and killed both the archduke and his wife.

The victims were not soldiers on a battlefield. They were civilians in a motorcade, killed during a political visit. Their deaths were the immediate trigger for Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war on Serbia, setting off a cascade of alliances that escalated into the First World War.

The war that followed claimed roughly 20 million lives, both military and civilian. In moral terms, any political ideology that celebrates the assassin while ignoring the mass death that followed engages in historical irresponsibility of the highest order.

The Chauvinist Myth of Princip

In some Serbian nationalist narratives, Princip is portrayed as a liberator or patriot. This framing typically rests on three ideological moves:

- Moral inversion: The victims are portrayed as legitimate targets because they represented imperial power.

- Historical fatalism: The First World War is depicted as inevitable, thereby minimizing the assassin’s role.

- Heroic martyrdom: Princip is transformed from a terrorist into a symbol of national liberation.

Such narratives are not merely historical interpretations. They function as political myths, teaching that violence against civilians can be justified if it serves nationalist goals.

This logic is ethically corrosive. It erases the victims and reframes murder as heroism. In doing so, it cultivates a political culture in which violence becomes a legitimate instrument of national destiny.

The Chain Reaction: From Sarajevo to Global Catastrophe

It is historically accurate that the First World War had multiple structural causes—alliances, militarism, imperial rivalries, and nationalism across Europe. However, the Sarajevo assassination was the immediate catalyst that allowed those tensions to erupt into war.

Without the assassination, the crisis of July 1914 would likely not have unfolded in the same way or at the same moment. The act of nationalist violence thus became the spark that ignited a geopolitical powder keg.

To glorify that spark is to celebrate the beginning of a global catastrophe.

A Recurring Pattern: Serbian Nationalism and the Yugoslav Wars

The logic of violent nationalism did not disappear after 1918.

In the 1990s, as Yugoslavia disintegrated, Serbian nationalist and irredentist movements again mobilized historical grievances and fears to justify armed conflict.

Scholarly analyses have argued that the Yugoslav wars were fueled by Serbian nationalist narratives that portrayed other ethnic groups as existential threats, thereby justifying aggression.

These narratives constructed a collective identity rooted in perceived historical victimhood and used it to legitimize violence against Croats, Bosniaks, and others.

The wars of the 1990s resulted in more than 140,000 deaths, mass rape, ethnic cleansing, and millions of refugees.

Scholars note that Serbian nationalist propaganda played a central role in escalating tensions and justifying violence.

Ideological Continuities: From 1914 to the 1990s

Despite the different historical contexts, striking parallels emerge between the glorification of Princip and the rhetoric of Serbian irredentism in the late twentieth century.

1. Mythologized Victimhood

Both narratives rely on the idea that the Serbian nation is perpetually threatened or oppressed, requiring extraordinary measures for survival.

2. Moral Justification of Violence

In both cases, violence is framed as defensive or liberatory, even when it targets civilians.

3. Historical Romanticism

The past is selectively interpreted to produce heroic narratives of struggle, often ignoring the human cost of nationalist violence.

The Ethical Problem of Heroizing Assassins

The glorification of Princip reveals a deeper ethical failure.

When a society celebrates political assassination, it normalizes the idea that violence against civilians can be justified for national goals.

This mindset:

- Encourages extremist politics.

- Dehumanizes perceived enemies.

- Undermines democratic norms.

- Repeats cycles of violence.

The lesson of 1914 is not that Princip was a hero, but that a single act of nationalist terrorism can unleash catastrophic consequences far beyond the assassin’s intentions.

Conclusion

The celebration of Gavrilo Princip among Serbian chauvinist narratives represents more than a dispute about historical interpretation. It reflects a persistent ideological pattern in which nationalist myth-making transforms acts of violence into symbols of liberation.

From Sarajevo in 1914 to the Balkans in the 1990s, chauvinist nationalism repeatedly framed violence as necessary and righteous—while producing immense human suffering.

A responsible historical memory must reject the cult of the assassin.

The true lesson of Sarajevo is not national heroism, but the terrifying ease with which chauvinist violence can ignite world-historical disasters.

References

On the Sarajevo assassination and World War I

- Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. London: Allen Lane, 2012.

- MacMillan, Margaret. The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. New York: Random House, 2013.

- Fromkin, David. Europe’s Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914? New York: Knopf, 2004.

- Dedijer, Vladimir. The Road to Sarajevo. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. Gavrilo Princip.

On Serbian nationalism and the Yugoslav wars

- Glenny, Misha. The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804–2012. New York: Penguin, 2012.

- Judah, Tim. The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

- Silber, Laura, and Allan Little. Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation. London: Penguin, 1996.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. Balkan Babel: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia from the Death of Tito to the Fall of Milošević. Boulder: Westview Press, 2002.

- Gagnon, V. P. The Myth of Ethnic War: Serbia and Croatia in the 1990s. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004.