By ROLAND QAFOKU

Abstract

This article reflects on a journalist’s firsthand encounter with a harrowing testimony from the Kosovo war in April 1999. It recounts the account of a mother and her two daughters who survived an alleged massacre committed by Serbian soldiers, including the killing of an infant during a raid on their home. The testimony was documented by Albanian prosecutors and reportedly submitted to authorities in The Hague. The author revisits this experience decades later in response to the prosecution’s request for lengthy prison sentences against former Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) leaders. The article contrasts the suffering of Kosovo Albanian civilians and the formation of the KLA as a defensive force with what the author portrays as a failure to prosecute Serbian perpetrators. It raises broader questions about justice, historical memory, accountability, and the role of international tribunals in addressing war crimes related to the Kosovo conflict.

Throughout my career as a journalist, I have reported on a wide range of events—both from the “black chronicle” of crime and the “white chronicle” of ordinary life. But what I experienced in April 1999 is beyond description in terms of its horror and the impact it left on me.

Amid the columns of Kosovar Albanians arriving in Tirana as part of that unprecedented genocide, I received a chilling testimony. It would be an understatement to describe the perpetrators of that Serbian campaign merely as cannibals, criminals, murderers, or exterminators of Albanians.

During a raid on homes in a village in Kosovo, Serbian soldiers stormed a house where a mother and her three children—aged 9, 5, and a baby only a few months old tied in a cradle—were alone. They were eating a simple meal, an ordinary soup of an ordinary family, when the soldiers burst into the dining room shouting and thirsting for blood.

Within minutes, two soldiers committed one of the most horrific and unheard-of crimes. They cut off the head of the crying baby in the cradle and put it into the pot of soup. The horror did not end there. Two other soldiers ordered the mother and the baby’s sisters “to eat the meat.”

It is difficult even to write such a scene in a newspaper, let alone to imagine how it unfolded in reality. Paradoxically, this extreme crime may have led to the survival of the mother and her two daughters, who fled their home in terror and escaped to Albania.

All three survivors were in severe shock at the refugee camp established in Tirana, where I witnessed their testimony describing what the Serbs had done to the Albanians of Kosovo. Fortunately, two Albanian prosecutors from the Office of the Prosecutor General recorded the mother’s and daughters’ statements and compiled the material in a substantial case file, which was then made available to prosecutors in The Hague.

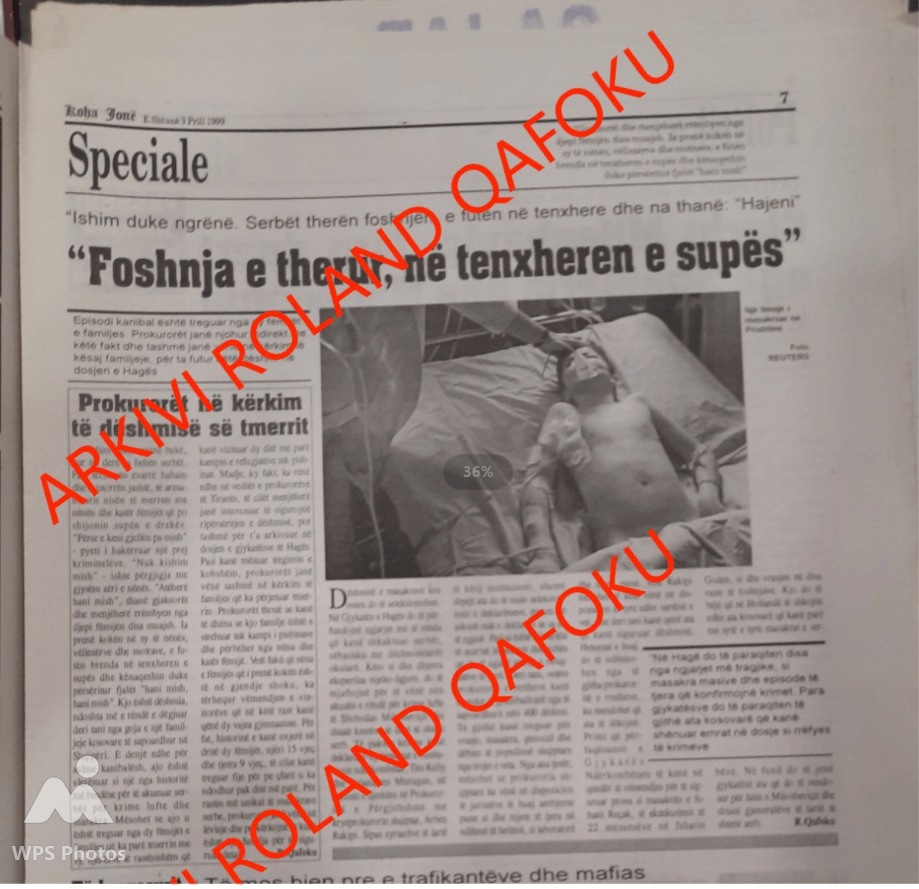

I published this testimony in the newspaper Koha Jonë, where I worked, in the April 3 issue of that year. It was perhaps the most difficult report I have ever written, both in terms of the experience and because it has never left my memory. Whenever Kosovo and the year 1999 are mentioned, I associate them with this event.

After 27 years, I retrieved it from my archive following the disturbance I felt upon hearing the prosecution’s request in The Hague to sentence Hashim Thaçi, Kadri Veseli, Jakup Krasniqi, and Rexhep Selimi to 45 years in prison. For what? Because, like many other young men and women, they took up arms and organized the KLA to defend their people. To defend even that baby whom, in fact, they were unable to protect from the Serbian criminals who beheaded it.

This single event—this scene whose horror surpasses even the most macabre Quentin Tarantino thriller—would be enough to condemn Serbian soldiers and generals for the greatest genocide committed in Europe since that of the Nazis against the Jews during World War II. But no. With yesterday’s indictment, the Hague prosecution instead sought extreme prison sentences for the KLA, which emerged from that martyred people of Kosovo to defend themselves.

Meanwhile, those cannibal soldiers are likely living peacefully in Belgrade, untouched and unpunished. With this demand, the prosecution has marked one of the greatest shames in the history of the Hague Court and of European justice. A shame that the court must correct.

The trial panel now carries the burden and the great challenge of overturning what appears to be a misguided prosecution in the heart of Europe that seeks to rewrite history. The spirit of that headless baby will remain restless until that day.