Abstract

This article examines war crimes where Serbian forces used poison gas against the Albanian population in Kosovo in 1918, situating the event within the broader context of World War I. While European powers deployed chemical weapons on battlefields across the continent, by 1918 the destructive effects of gas were well documented, and post-war protocols would soon formally ban their use. The deployment of poison gas against civilians, particularly in a region already scarred by years of repression, represents a deliberate moral transgression. This case highlights the extension of wartime atrocities beyond conventional battlefields and underscores the ethical collapse that can follow unchecked militarism.

When Europe choked in the trenches from poison gas, the Serbian military used it on Albanian civilians in 1918.

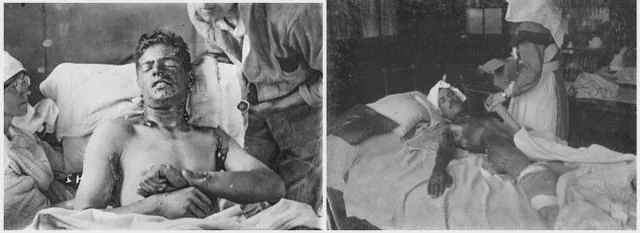

World War I was not merely a conflict of armies. It was the industrialization of death. Across Europe, poison gas drifted over battlefields like a second, invisible artillery barrage — chlorine clouds rolling over Ypres, phosgene seeping into trenches, mustard gas blistering lungs and skin beyond recognition. Soldiers coughed up blood. Eyes burned blind. Skin peeled from bodies in chemical agony. Entire regiments were reduced to gasping wreckage, their survival measured not in victory, but in how long they could endure suffocation.

Every major European power bears the stain of chemical warfare. Germany initiated it on a large scale in 1915. France and Britain retaliated. Russia deployed it. Austro-Hungarian forces used it. The war became a laboratory of horror where morality collapsed under the excuse of “military necessity.” Europe burned — and it poisoned itself while doing so.

But even within this abyss, there were lines that civilized nations claimed to recognize: poison gas was a weapon of war, used against enemy soldiers in uniform, however grotesque and indefensible that use may have been.

And yet, according to the German newspaper Westdeutsche Landeszeitung: Gladbacher Volkszeitung und Handelsblatt: allgemeiner Anzeiger für den gesamten Niederrhein: die Niederrheinische Heimatzeitung, Serbian troops used poisonous gas in Kosovo in 1918.

If true, this was not trench warfare between industrial empires locked in symmetrical slaughter. This was not Verdun. This was not the Somme. By 1918, Europe was already exhausted, shattered, morally bankrupt from four years of mechanized brutality. The continent had seen enough mutilation to last centuries. And still, in Kosovo, poison entered the picture — not against massed armies in a battlefield stalemate, but against a vulnerable Albanian population already subjected to years of repression and violence dating back to 1912.

The Balkan Wars had already left Kosovo scarred. Reports from that period documented reprisals, expulsions, and atrocities against Albanian civilians. The First World War did not erase those tensions; it deepened them. So when chemical weapons — the most infamous symbol of wartime barbarity — have been turned on that region in 1918, the act carries a different moral weight. It suggests not desperate battlefield escalation between rival empires, but the extension of Europe’s worst weapon into a setting where civilians bore the consequences.

Let us be clear: poison gas was a crime against humanity wherever it was used. The soldiers who stumbled blindly through chlorine clouds in Flanders were victims of moral collapse at the highest levels of command. But there is a qualitative horror in the idea of chemical agents deployed in Kosovo after years of ethnic violence — against a population already battered by occupation and war.

By 1918, Europe had learned exactly what gas did to human flesh. It was no longer an experimental unknown. Its effects were documented in gruesome detail: lungs dissolved from within, blisters forming on children and adults alike, lingering illness that followed survivors to early graves. To employ such a weapon at that late stage of the war, in a region wracked by ethnic hostility, would have represented not ignorance — but choice.

The tragedy of World War I is often framed as shared madness — a continent sleepwalking into catastrophe. But sleepwalking does not explain persistence. It does not explain the continuation of cruelty after its consequences were unmistakable.

If these reports are accurate, then the use of poisonous gas in Kosovo in 1918 stands as a chilling reminder that the Great War did not merely brutalize Europe’s battlefields; it corroded moral boundaries everywhere it touched. It normalized the unthinkable. It allowed states to justify methods that, only years earlier, would have been universally condemned.

Europe’s gas warfare remains one of the darkest chapters of the 20th century. It disfigured tens of thousands and haunted survivors for life. That legacy alone should have been enough to restrain further descent. Instead, the war’s final year allegedly saw its most infamous weapon reach beyond the trenches into a region already scarred by years of violence.

The lesson is not selective outrage. It is collective indictment. When nations decide that survival or dominance justifies anything, civilians become expendable, and science becomes a servant of cruelty.

World War I proved that Europe could poison itself. The war crimes concerning Kosovo suggest something even more disturbing: that in the chaos of total war, the poison did not always stop at the battlefield.

Haag Convention of 1899 and 1907

It is important to understand the legal context. Even before the First World War, the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions had attempted to prohibit the use of projectiles designed solely to spread asphyxiating gases, though these restrictions were vague and often ignored during the conflict. After the war, in 1925, the Geneva Protocol formally banned the use of chemical and biological weapons in warfare.

This prohibition was born directly from the documented horrors of World War I — the burned lungs, blistered skin, and permanent suffering of its victims. Later, the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention expanded the ban to include development, production, stockpiling, transfer, and use of chemical weapons, entering into force in 1997.

Source

“Serbian troops are using poisonous gas in Kosovo in 1918.” “Westdeutsche Landeszeitung : Gladbacher Volkszeitung und Handelsblatt : allgemeiner Anzeiger für den gesamten Niederrhein : die Niederrheinische Heimatzeitung”. 1912.