Persecution of Albanians in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The persecution of Albanians in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia included mass murders, executions, burning of villages, looting, rape, torture, imprisonment, deportations, and forced expulsions of Albanians by military and paramilitary forces during the rule of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[1] These crimes followed previous massacres of Albanians in World War I and massacres of Albanians in the Balkan Wars by Serbian, Montenegrin, and Yugoslav forces.

According to historian Miranda Vickers, between 200,000 and 300,000 Albanians were expelled from Yugoslavia during the interwar period, while Noel Malcolm estimates the number to be between 90,000 and 150,000. Hakif Bajrami [sq] estimated that around 240,000 Albanians were deported from Kosovo from 1918 to 1941.[2]

Tens of thousands of Albanians were killed in Kosovo, Macedonia, and Montenegro during the interwar period. Approximately 60,000–77,000 Albanians were killed from 1918 to 1921.[1][3][4] According to Hakki Demoli, 80,000 Albanians were killed by 1940.[5]

Background

Many Albanians in Kosovo and Albania resisted integration into the often changing Yugoslav regimes, knowing that the new Yugoslav forces were the same Serbo-Montenegrin troops that had committed massacres of defenseless civilians. Albanians considered peaceful coexistence unattainable given the terror and violence they had experienced.[6][7]

After World War I, Serbia suffered greatly from the Austro-Hungarian occupation, and Kosovo was the scene of conflict between Albanians and Serbs. In 1918, the Allies in World War I rewarded Serbia for its efforts by forming the Serbian-centralized Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which retained Kosovo as part of Serbia.

Conditions for Kosovo Albanians worsened as Serbian authorities implemented assimilation tactics, such as closing Albanian-language schools, while simultaneously encouraging Albanians to emigrate. The kingdom promoted the settlement of Serbian and Slavic settlers in Kosovo, beginning the Yugoslav colonization of Kosovo.[6]

Parts of the Albanian population resisting Serbian rule in Kosovo began military maneuvers and formed the Kaçak Movement. Under the political leadership of Hasan Priština and Bajram Ćuri, the movement was based in Shkodra and led by the Kosovo National Defense Committee.[8] Among their demands were the reopening of Albanian-language schools, recognition of Albanian as a second official language, and autonomy,[8] with the goal of unifying Kosovo with Albania.[9]

The Kačaks launched an uprising, targeting the Serbian army and administrative formations, but forbade their members from targeting unarmed Serbs and churches.[8][10] The Serbian authorities considered them to be ordinary bandits and in response to their rebellion, retaliated with operations against them, as well as against the civilian population.[8] In 1919, a major uprising in Drenica, led by Azem Galića, involving 10,000 people, was suppressed by the Yugoslav army.[10] By 1924, military conflicts between Albanians and Serbs had ended, and the Kačak movement had been effectively suppressed.[8]

Kosovo massacres ,

Ćipeva.

On 28 May 1919, Serbian forces massacred 22 Albanians and a two-year-old child in the Ćipeva region, in the Damanek and Bubel regions. A young Albanian named Halili and Vogel “Mali Halil” survived.[11]

Gurabardi and Zatrić

In June 1919, Serbian Chetniks led by Colonels Katanić, Babić and Stanko attacked the village of Lapuša, allegedly in pursuit of Kačacs who lived in the Gurabardi mountains. The inhabitants were massacred. The Serbian detachment had just arrived after the massacre in Zatrić where 27 Albanians were bayoneted, one of the village elders was beaten to death, and another had his eyes gouged out.[12][verification needed]

Konjuhi massacre

In 1924, Yugoslav forces entered the village of the Albanian Konjuhi family and massacred the entire family.[13]

Mitrovica

In 1924, two villages were destroyed and 300 families were killed.[14] Between 1919 and 1921, approximately 1,330 Albanians were killed in Mitrovica.[15]

Pristina

According to Albanian newspapers, in the province of Pristina, Serbian troops killed 4,600 people, imprisoned 3,659 people, beat 353 people, destroyed 1,346 houses, and looted 2,190 houses.[16]

Dubnica

By order of Commander Petrović and County Governor Likić, the village of Dubnica was surrounded and burned on February 10, 1924. Yugoslav authorities massacred 25 people: 10 women, 8 children under the age of eight, and 6 men over the age of fifty.[17]

Rugova

In 1919, Yugoslav forces committed many atrocities in Rugova. From 25 December 1918 to early March 1919, approximately 842 Albanians were killed, including women, the elderly, children, and infants.[1][18]

Kečekole

In January 1921, Yugoslav forces committed numerous crimes against the Albanian civilian population of Kečekole and Prapaštica.[19][20]

Duškaja

In 1921, a massacre was committed by Serbo-Montenegrin military and paramilitary Chetniks against the Albanian population in the village of Jablanica in the Duškaja region. The perpetrators were Kosta Pećanac, Milić Krstić, Spire Dobrosavljević, Arseni Ćirković, Gal Milenko, Nikodim Grujići and Nove Gilići. 63 civilians were killed during the day.[21]

Peć

In Peć, 1,563 Albanians were massacred and 714 houses were destroyed from 1919 to 1921.[15]

Prizren

In Prizren, between 1919 and 1921, around 4,600 people were killed and 2,194 houses were burned down.[15]

Ferizaj

From 1919 to 1921, approximately 1,694 people were massacred in the Ferizaj area.[15]

Podgur

On 15 December 1919, a Montenegrin Chetnik detachment attempted to disarm an Albanian merchant in the village of Podgur, resulting in the burning of 138 houses and the looting of 400. In addition, women, children and elderly men were massacred.[22][1]

Montenegro

Hoti

On 25 December 1919, Montenegrin commander Savo Pjetri arrived in Hoti in the Kuše region of Điteka with his army. 72 Albanians were arrested and sent to Prekaljaj, held overnight, and then executed the next morning and thrown into a mass grave, in the hope of hiding the crime.[23][24] On 7 December 2019, relatives of the Hoti in the United States held a memorial service for the victims.[25][26]

Plav and Gusinje

On 25 March 1919, the Kosovo Committee sent a report in French to the British Foreign Office stating that between 17 and 23 February 1919, Serbo-Montenegrin troops massacred the population of Plav and Gusinje.[27] The Yugoslav authorities had massacred 333 women, children and elderly men by March 1919.[1]

Rožaje

In February 1917, Serbo-Montenegrin troops massacred 700 Albanians in Rožaje and 800 in the Đakovica area, and destroyed 15 villages in Rugova with artillery.[1]

Historical data

According to the Albanian newspaper “Dajti” from 7 November 1924 and data from the Archives of the National Defense Committee of Kosovo, between 1918 and 1921, several massacres of the Albanian population occurred.[28][29][30]

The United States Department of State reported widespread massacres in Montenegro in May 1919. The information was obtained by Albanian refugees in Shkodra and collected by Lieutenant Colonel Sherman Miles. The massacre was over and Montenegro was “completely cleansed” of Albanians two months before his visit to the province. According to Albanian refugees, about 30,000 Albanians had been killed in Montenegro by May 1919. The British mission in Shkodra, however, estimated this figure at 18,000–25,000.[1]

In July 1919, the French consul in Skopje reported nine massacres with 30,000–40,000 victims and that Albanian primary schools had been closed again and replaced with Serbian schools.[3]

Around 35,000 Albanians fled to Shkodra as a result of the atrocities.[31] According to Sabrina P. Ramet, approximately 12,000 Albanians were killed in Kosovo between 1918 and 1921, which is consistent with the Albanian claim that 12,346 people were killed.[32][4][33] More than 6,000 Albanians were killed by Yugoslav forces in January and February 1919.[34] Around 2,000 “Albanian patriots” were killed in Kosovo between 1919 and 1924. This number rose to 3,000 between 1924 and 1927.[35] According to the Kosovo Albanian politician Haki Demoli, 80,000 Albanians were “exterminated” in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by 1940.[5]

International reactions

The Swiss newspaper La Jeune République published an article by Louis Rocher on 25 September 1921, which mentioned Yugoslav crimes against the Albanian population.[36]

In June 1919, the Italian commander Piacentini sent a telegram reporting that Serbian troops were “burning villages and massacring women and children”.[37]

References

- Department of State, United States of America (1947). Papers Relating to Foreign Relations of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 740–741. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- Rama, Shinasi (2019). Nation Failure, Ethnic Elites, and the Balance of Power: The International Administration of Kosovo. Springer. p. 107. ISBN 978-3030051921. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Correspondence on the aggression against Yugoslavia. Faculty of Law, University of Belgrade. 2000. ISBN 978-86-80763-91-0. Accessed August 19, 2023.

- Ramet, Sabrina Petra (February 19, 2018). Balkan Babylon: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia from Tito’s Death to the Fall of Milošević, Fourth Edition (more than 12,000 Kosovo Albanians were killed by Serbian forces between 1918 and 1921, when pacification was more … ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-97503-5. Accessed August 19, 2023.

- Demoli, Haki (2002). Terrorism. Pristina: Faculty of Law, Pristina. “Based on national secret files, in the period 1918-40, around 80,000 Albanians were exterminated, between 1944 and 1950, 49,000 Albanians were killed by communist Yugoslav forces, and in the period 1981-97, 221 Albanians were killed by Serbian police and army. During these periods, hundreds of thousands of Albanians were forcibly displaced to Turkey and Western European countries.”

- Geldenhuys, D. (22 April 2009). Disputed States in World Politics. Springer. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-230-23418-5. Retrieved 19 August 2023. “[…] the annexation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (meaning the South Slavs) in 1929 brought no respite to the persecuted Albanians. The reprisals to which they were subjected (including massacres) continued the now familiar cycle of hardship.”

- Bytyci, Enver (1 April 2015). NATO’s Coercive Diplomacy in Kosovo. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4438-7668-1. Accessed 19 August 2023.

- Lenhard, Hamza (2022). The Politics of Ethnic Adjustment: Decentralization, Local Government and Minorities in Kosovo. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 62. ISBN 9783643912251.

- Tasić, Dmitar (2020). Paramilitarism in the Balkans: Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Albania, 1917-1924. Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780198858324.

- Robert Elsey (15 November 2010), Historical Dictionary of Kosovo, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, vol. 79 (2nd edition), Scarecrow Press, p. 64, ISBN 978-0810872318

- “Songs of the popular and Turjakes”. DRINI.us (in Albanian). January 25, 2023. Accessed August 21, 2023.

- Yetish Kadishani “Masakra e Gurbardhit” (Masakr Gurabardhija). Bujku, Pristina. August 28, 1997, p-8.

- Pllanaj and Emin Kabashi, prof. dr Nusret (2001). Terror of the invasion of Serbia over the Albanians 1844-1999. Pristina: Archives of Terror and Kosovo. ISBN 9951404006. Accessed 21. 8. 2023.

- The practice of bourgeois class justice in the struggle against the revolutionary movement of workers, national minorities and colonial and semi-colonial peoples. Publishing House Mopr. 1928. Accessed August 19, 2023.

- Plana, Nusret; Kabashi, Emin (2001). Der Terror der Besatzungsmacht Serbien gegen die Albaner (in Albanian) (1918-1921, sont tues beaucoup d’albanais ainsi que leurs maisons brûlées Dans la prefecture de Peja 1563 personnes tues et 714 personnes tues et 714 Mitrovica et 42 maisons brûlées ed.). Shteteror i Kosoves Archives. p. 33. ISBN 978-9951-404-00-6. Accessed 19 August 2023.

- (Facsimile taken from the newspaper “Dajti”, the names and tables of the newspapers, which show the atrocities committed by Serbs against Albanians in 1918-1921.) Albanian newspaper “Dajti”. Title: Summary of crimes committed by Serbian forces in Kosovo (October 15, November 18, November 11, number killed 19.19). Pristina: 4,600 victims: 3,569 (taken from the Archives of the Kosovo Committee).

- Elsey, Robert. “Memorandum on the Position of the Albanian Minority in Yugoslavia Submitted to the League of Nations.” albanianhistory.net.

- Statistics of the Rugova Massacre”. http://www.albanianhistory.net .

- Sherifi, Remzije (2007). Shadow Behind the Sun. Peshčar. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-905207-13-8. Accessed August 19, 2023.

- Studia Albanica (in French). L’Institut. 1981. p. 74. Accessed August 19, 2023.

- Krasniki, Mark (1984). Lugu and Baranit: ethno-geographic monographs (in Albanian). Academy of Sciences and Arts of Kosovo. p. 37. Accessed 19 August 2023.

- Jarman, Robert L. (1997). Yugoslavia: 1918-1926 (A Montenegrin detachment attempted to disarm an Albanian merchant. On December 15, the massacres of Podgur took place. 138 houses were destroyed; 400 houses were looted. Villagers and massacres of children.) ed.). Archive Editions Limited. pp. 165. ISBN 978-1-85207-950-5. Accessed August 19, 2023.

- Camaj, Albert (December 24, 2019). “MALESIA.ORG – Tuz, Malesi – JUNCAI: 100 WINDS AND MASSACRE IS INTENDED”. MALESIA.ORG – Tuz, Malesi. Accessed August 21, 2023.

- Hoti Massacre Commemorated; Albanian-American Prosecutor John Juncaj: End of 100 Years of Silence”. Oculus News. December 7, 2019. Accessed August 21, 2023.

- “Perkujtohet masakra e Hotit/ “I am the victim and the victim”, prosecutors of the Skript-American: Fund hashtjes 100-vecare”. http://www.balkanweb.com (in Albanian). Accessed 21 August 2023.

- K, Zvezda Plus (December 7, 2019). “MASSACRAMENT IS INTENDED, SHKIPTAR AND SHBA PROSECUTORS: EVERYONE IS ANGRY”. STAR PLUS TV – SHKODER. Accessed August 21, 2023.

- Elsey, Robert; Destani, Bejtullah D. (January 30, 2018). Kosovo, a Documentary History: From the Balkan Wars to the Second World War. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78672-354-3. Accessed August 19, 2023.

- Šaban Braha, Genocides of Serbs by the Kendras of the Skripta (1844-1990), Lumi-T, Đakovica, 1991, pp. 225-375.

- Hamit Borici, His Life as a Writer of the Skripta (1848-1997), Tirana, 1997, pp. 84-85.

- Blendi Fevziu, History of the Shtipit Shkeptar 1848-2005, Onufri, Tirana, 2005, p. 60.

- Department, Federal Research Library of Congress (1994). Albania: A Country Study. Federal Research Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8444-0792-0. Accessed 19 August 2023.

- Biber, Florian; Daskalovski, Zidas (2 August 2004). Understanding the Kosovo War. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-135-76155-4. Accessed 19 August 2023.

- Middle East. 1921. Accessed August 19, 2023.

- Phillips, David L. (July 20, 2012). The Liberation of Kosovo: Coercive Diplomacy and US Intervention (Serbian troops clashed, killing more than 6,000 Albanians – ed.). MIT Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-262-30512-9. Accessed August 19, 2023.

- (RSH), Institutes and Histories (Akademia e Shkencave e) (1993). Truth in Kosovo. Encyclopedia Publishing House. Accessed August 19, 2023.

- Shkrim i vitit 1921, per krimet Serbe ne Kosove: Tokat u dojen, popullata u masakrua, pronat u plackiten!”. Telegrafi (in Albanian). 2. March 2020.

- Motta, Giuseppe (25 March 2014). Less than Nations: The Minorities of Central and Eastern Europe after the First World War, Volumes 1 and 2. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-4438-5859-5. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

Persecution of Albanians in Yugoslavia (1941-1999)

The persecution of Albanians in Yugoslavia (1941–1999) refers to the persecution of Albanians in Kosovo from 1941 to 1999 in Yugoslavia. At the beginning of the federation, Partisan, Chetnik, Bulgarian and Yugoslav troops committed a series of massacres and atrocities against Albanians. In the 1950s, Aleksandar Ranković, head of the Yugoslav secret service, expelled, killed or imprisoned thousands of Albanians during the “1955–56 arms roundup”.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Serbian nationalism under Milošević and Albanian protests demanding independence led to repression by Yugoslav authorities and ultimately to war. Many Albanians were killed and expelled during this period. The persecution of Albanians officially ended in 1999 when Yugoslavia was bombed and KFOR forces entered Kosovo.

Background

This was a continuation and part of the Massacre of Albanians in the Balkan Wars, the Massacre of Albanians in World War I, and the Persecution of Albanians in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Before the federation, Albanians in Kosovo were the most marginalized ethnic group and victims of systematic discrimination and various forms of pressure to leave the region.[1] Between 1937 and 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia established a program to expel 200,000 Albanians to Turkey, which was interrupted when World War II began.[2] When World War II began, Albanian nationalists in the Balkan Combatant Army in Kosovo fought alongside Germany and Italy and hoped to reunite Kosovo with Albania, a goal that was achieved when Benito Mussolini secured the establishment of a “territorially and ethnically united Albania”.[3]

The policy towards the Albanian population was initially a copy of the national policy introduced in the USSR. Despite a similar ideology, aimed at eliminating the “class enemy”, a state of emergency was introduced in Kosovo, which lasted until the beginning of 1946. Thus, although the Albanians were guaranteed equal rights with other peoples in Yugoslavia by the constitution, in reality they were denied them. But they did not accept this situation peacefully and expressed their disagreement with various forms of resistance.

Hoping to attract the loyalty of the communist regime in Albania, Josip Broz Tito envisioned the unification of Kosovo with Albania, but this was stopped by Serbian propaganda and fear, although Tito was convinced by Lenin’s doctrine that Serbian nationalism (i.e., the nationalism of larger nations) was more dangerous than smaller ones (i.e., Albanian nationalism).[4] Tito remained an opponent of Serbian hegemony on this issue.

Assimilation policy and discrimination

When Kosovo was handed over to Yugoslavia, Albanians protested. Many Albanian nationalists were killed, imprisoned, or executed, and many were expelled or fled. Although Kosovo was declared autonomous within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the province’s policymaking capabilities remained very limited in reality. Effective legislative power was exercised by Serbia. From 1945, policy goals for Kosovo were aimed at assimilating the Albanian population and changing the cultural characteristics of Kosovo. Attempts at assimilation failed because Kosovo Albanians continued to speak Albanian.[5]

666 centuries of imprisonment

In the 1980s, 80% of all political prisoners were Albanians, illustrating the scale of the persecution.[6][7][8][9]

Between 1945 and 1990, over 8,220 Albanians were sentenced to prison terms totaling 66,672 years and 7 months, or 666 centuries, 72 years and 7 months. The average sentence per person was 7 years and 1 month. In the period 1981–1990, 3,348 people were sentenced to prison, and 23,770 to 8 years. Another 10,000 were sentenced for misdemeanors, or 1,233 years. During this period, another 1,346 Albanian soldiers were sentenced, while 63 were killed in the barracks. From March 1981 to October 1989, 584,373 Albanians were abused by the police. Violence was used, such as threats and beatings to the point of unconsciousness.[10]

In 1945, over 2,086 people were sentenced to prison in Kosovo, totaling 14,810 years and 6 months. In the period 1956–1980, 901 people were imprisoned and sentenced to 6,397.1 years in prison. During the period 1981–1989, one in three Albanians passed through the hands of the Yugoslav police.[11] After the 1981 demonstrations, 3,348 people were sentenced to 25,000 years in prison. Some 1,346 Albanian soldiers were sentenced to 955 years and 6 months in prison, and 63 of them returned home in coffins.

Massacres

According to the Albanian press, around 36,000 Albanians were killed by Tito’s partisan forces after World War II.[12][13]

In early 1945, Yugoslav authorities illegally and without trial shot more than 1,000 Albanians from Kosovo on the territory of the Albanian state.[14] Many Yugoslav crimes were proven by high-ranking officials of the Albanian state such as Nesti Kerendži, a former deputy minister of the interior, Lieutenant Colonel Zoi Temeli, a former high-ranking official of the State Security, and Šefćet Peći. Between 1944 and 1946, in the city of Mitrovica, more than 2,000 Albanians were massacred by the Yugoslav 6th Kosovo Brigade.[15]

Mitrovica Massacre

Between 1944 and 1946, in the city of Mitrovica, more than 2,000 Albanians were massacred by the Yugoslav 6th Kosmet Brigade.[16]

Vushtrri Massacre

400 bodies were found in the town of Vushtrri.[17]

Gostivar massacre

In November 1944, more than 1,000 people were shot between Kosovo and Tetovo. In Gostivar, Yugoslav officers killed 300 Albanians after taking them out of the barracks. In December 1944, 70 people were arrested in this town and shot on a hill called Gradishtan. On November 17, 1944, about 10,000 Albanians gathered at the tobacco monopoly station in Tetovo, and many of them were shot that same night.[18]

Kirčovo massacre

320 Albanians were killed in the village of Kirčovo. Another 300 boys were taken from Skopje under the pretext of being sent to a military unit, but they never returned.[19]

Massacres in Skopje

Many massacres occurred in the Skopje area. In the village of Bojane, 76 men and 30 women and children were killed, while in the village of Blace, all the men (160 people) and 50 children were killed, and the village was burned.[20][21]

Massacres in Drenica

According to the newspaper “Zeri i Populli”, Tito’s men tore up and threw away the Albanian flag and began mass shootings and unprecedented terror in the Drenica region. Children and pregnant women were shot and hanged, people were left hanging on stilts, and many died from torture. Hundreds of Albanian conscripts were shot on the Prizren-Kukeš-Tirana road. In the Gorica region of Trieste, more than 2,000 Albanian boys from Macedonia, mobilized into labor brigades, were killed with poison gas.[22]

Đakovica massacre

Yugoslav forces killed 20 Albanians from the Đakovica plateau.[23]

Bihor massacre of 1943.

With the support of Italian forces, Serbo-Montenegrin forces, under the command of Pavle Đurišić, razed 82 villages in the Bihor province of the Sandžak on 5 and 6 January 1943. Albanian archival documents reveal that 4,628 Albanians were massacred in 2 days.[24] Hundreds of others, mostly women and girls, were captured. 15,000 were forced to flee. The region was under the protectorate of the Italians, who permitted the massacre.[25] Other sources state that 9,200 Albanians were killed.[26][27] There are also Bosnian sources that confirm the crimes.[28][29]

The Albanian delegation investigated the case and concluded that 590 men were killed, 185 were slaughtered, 119 were bayoneted. 340 women were killed, 285 were stabbed, 266 were cut into pieces. 701 children were killed, 705 were burned, and 447 were torn apart. 359 men and 275 women were injured. 250 young women were deported to Chetnik camps under the control of Draža Mihailović, where they were raped. The sources were taken from the Central State Archives in Tirana, in the 1943 archive fund, item number 5, with 57 sheets. Some original documents were sent to Prime Minister Ekrem Bey Libohova at that time.

Gnjilane massacre in 1942.

In the village of Blace, Kačanik, a Macedonian partisan brigade shot 128 Albanians. Another 128 Albanians were found in a mass grave, several of whom had their throats slit. On 15 November, 109 victims were discovered, and the next day, 8 more. On 25 July 1942, the village headman of Gnjilane reported that the survivors had arrived without clothing, shelter, and were sleeping in open fields. When Bulgarian forces invaded the region, the Albanians took up arms and various battles ensued.

On 15 September 1943, Serbian commander Jagod and his Chetnik forces bombed the Preševo mosque on the night of Ramadan, killing four and wounding 28. They also massacred civilians in Iseuka, Gosponica and Sopot. In the village of Koka, Imer Saćapi was wounded in the direction of the village of Kokaj, where he died and was buried in the cemetery. Several Albanians died of their wounds, among them Ahmet Haziringa Ljovac, Rifat Lipovica on 14 December 1944. The grave is unknown to the victims of Gjilan.

On 28 November 1944, when mobilized Serbian forces of the 3rd Preševo Brigade entered the village of Gosponica, Rustem was killed along with 33 residents of Gosponica and Bukuroča.[30]

In the town of Gnjilane, 1,000 people were shot, and in Skenderaj 250. In the Polish village of Uroševac, 28 people were shot in front of their families. Near Priština, in a place called Tomboce, over 200 people were shot, while 70 people were massacred in Priština in one day. In Peć, 200 Albanian men were killed from December 1944 to early 1946.[31]

Rogovi massacre of 1941

In April 1941, Catholic Albanians from 8 villages in Đakovica were massacred in Rogovi. The crimes were documented in a book titled “Trojet e Arberis” by Dom Viktor Sopi.[32] 64 Albanians were killed from the villages of the Smać parish: Bistažini, Berdosana, Dolji, Fšaj, Kusari, Kušaveći, Marmuli and Smaći. The perpetrators were Serbian commanders Srećko Čemerikić and Brajan Zorić.[33]

Preševo massacres 1941–45.

On 18 April 1941, Bulgarian troops massacred 341 Albanians, imprisoned 790 people, and burned 650 houses in Preševo.[34] In Bujanovac, troops killed 649 civilians and burned 1,180 houses.[35] In Preševo and Kumanovo, during the first half of 1945, about 600 members of the Albanian population were arrested, of whom about 200 were killed on the way to the city of Vranje, while the rest drowned in the prison in Vranje. Many others were also shot in the city of Preševo.

Massacres in Gosponica, Kari and Iseukaj

Most of the crimes committed by the Serbian-Macedonian communists were committed at night, accompanied by music to drown out the screams of the tortured children and women.[36] In Iseukaj, all the men were killed. In Gosponica, 8 people were killed. On 22 December 1944, the brigades massacred 24 Albanians in the village of Kari and burned 50 houses.[37][38][39]

Skopje Massacres

On 6 October 1944, in the village of Blace in Skopje, the 16th Yugoslav Brigade killed 111 Albanian civilians, and the bodies were left unburied for several days.[40] The perpetrator was Gliša Šaranović. Approximately 7,845 people were killed in Gnjilane.

Bar massacre in 1945.

In 1945, Montenegrin communists massacred thousands of Albanian men in Bar.

The 1955–56 arms confiscations, initiated

by Aleksandar Ranković, the head of the Yugoslav secret service, ushered in a period of systemic discrimination. Ranković’s paranoia and racist, fanatical obsession with targeting Albanians in Kosovo led to the so-called “1955–56 arms roundup”, in which thousands of Albanians were imprisoned, exiled, or killed and tortured to death by having their heads placed in ovens until they were burned alive. According to Albanian sources, as early as 1945–46, around 12,000 Albanians were under the surveillance of Ranković, who considered Albanians “informburoists”, a term that means something like “spies”.[41]

Public Executions

Until 1952, the Yugoslav communists continued to hold show trials and carry out public executions of Albanians, in an effort to intimidate small groups that violently resisted Yugoslav rule in Kosovo. Evidence suggests that the police, in collaboration with state security, systematically resorted to reprisals and abuses, thereby violating constitutional and other legal limits during the operation. For example, Budimir Gajić, in his capacity as mayor of Prizren, described the process in an internal report from 1956 as follows:

“…

We showed persistence in calling people and holding them until they surrendered their weapons, 4-5 days. There were also cases where people were held for 4-5 days in the snow and beaten. Similarly, the testimonies of witnesses who participated in the confiscation, both officials and civilians, reveal the use of systematic beatings of those suspected of possessing firearms.”[42]

According to Albanian sources, Ranković’s goal was to increase pressure on Albanians to leave for Turkey.[43] Many Albanians did not own weapons, but were forced to find a rifle and surrender it in order to end the harassment.

The aim of the operation was to spread fear in rural Kosovo. Yugoslav repression of Albanians had led to the deaths of thousands, and many fled to Turkey. According to sources found in the Archives of the Kosovo State University Agency (ASHAK) and the Regional Historical Archives of Đakovica, Ranković was eventually displaced after reports of deformities and abuse of Albanians were published. Another purpose was Ranković’s desire for ethnic chauvinism.[44] There are reports of Ranković’s men using lies to brainwash young Albanian boys that a certain village elder (whom Ranković wanted removed) had killed the boy’s father. Ranković’s men would then arm the boy and he would proceed to kill the target.[45]

Expulsions

Between 1953 and 1967, 408,000 Albanians were expelled as a result of Ranković’s policies. Around 30,000 people were subjected to torture, 103 people lost their lives as a result of this torture, and approximately 10,000 people were left with lifelong disabilities.[46]

Ranković also minimized and downplayed the Bar massacre of 1945.[47]

Yugoslav assassinations of important Albanian officials

In order to destabilize the situation of Albanians, the Yugoslav authorities carried out a series of assassinations and murders during the Ranković era.

Xheladin Hana

Xheladin Hana, an Albanian patriot, was arrested and tortured, then killed on December 15, 1948.[48][49]

Nexhat Agoli

Nexhat Agoli, Deputy Prime Minister of the Macedonian government, originally from Veliki Debar, was arrested on April 15, 1949 and was strangled by Ranković’s men.[50]

Rifat Berisha

Knowing that the Yugoslav secret police, led by Čedo Topalović and Čedo Mijović, were pursuing Rifat Berisha, the Albanian nationalist president, he decided to fight in the Drenica hills on 17 May 1949.[51][52] The village of Gajrak was surrounded and the Albanians fought the Yugoslav troops all night until they were massacred.[53]

Sabaudin Đura

In the winter of 1950, Albanian patriot Sabaudin Đura was killed, as was Isuf Torozi, who had been arrested in 1949 and tortured to death.[54][55]

Cene Shikriu

In March 1949, Cene Shikriu from Gjakova was arrested and disappeared without a trace.[56]

Murders of 1981

In 1981, Albanian students were murdered and poisoned in Mitrovica, Vustrovo, Ferizaj and Pristina by Yugoslav police.

Crisis of 1997

According to author Jane Sharp, after Tito’s death in the 1980s, Slobodan Milošević exploited resentment against Kosovo Serbs to foment hatred. Dr. Mary Kaldor of the London School of Economics has noted that the main conflict of the 1980s and 1990s can be traced to Milošević’s “insisting on the mystical significance of Kosovo”,[57] part of a larger Serbian propaganda developed by Serbian intellectuals. The Kosovo myth was inflated and turned into a tool of oppression.

Massacres of 1998–99.

Serbian-Yugoslav forces committed many massacres against the Albanian civilian population during the 1998–99 Kosovo War.

References

- Cvić, Christopher (2005). Kosovo 1945-2005. pp. 851–860. Accessed 23 August 2023.

- Jeta, Loshaj. “Kosovo and Ukraine are more similar than many people think.” Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- STAMOVA, MARIJANA (2017). THE ALBANIAN FACTOR IN SERBIA/YUGOSLAVIA IN THE 19TH AND 20TH CENTURIES (What Albania could not achieve as an independent state, namely the unification of the entire Albanian nation in one state, was actually finalized by Benito Mussolini’s decree of June 29, 1941, which envisaged the establishment of a “territorially and ethnically united Albania” under the Italian protectorate. ed.). Institute of Balkanology and Center for Thracology, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- T. BATAKOVIĆ, DUŠAN. The Case of Kosovo: Separation versus Integration Heritage, Identity, Nationalism. Belgrade: Institute of Balkan Studies, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. p. 109. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. “Refworld | Assessment of Kosovo Albanians in Yugoslavia”. Refworld.

- Matas, David (26 July 1996). The End: The Struggle Against Human Rights Violations (Almost half of the political prisoners in Yugoslavia were ethnic Albanians imprisoned for claiming to identify with the Albanian nationalist cause. Albanian nationalism does not appear so much as a desire to join neighboring… ed.). Dandurn. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4597-1847-0.

- Dolečki, Jana; Halilbašić, Senad; Hulfeld, Stefan (November 19, 2018). Theatre in the Context of the Yugoslav Wars (As a result, three out of every four ordinary prisoners in Yugoslav prisons at that time were Albanian political prisoners from Kosovo. Sabile KečmeziBaša explains that the Albanians of the former Yugoslavia spent 666 centuries, 72 years and 7 … ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-98893-1. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- Pichler, Robert; Grandits, Hannes; Fotiadis, Ruža (September 1, 2021). “Kosovo in the 1980s – Yugoslav Perspectives and Interpretations”. Comparative Studies of Southeast Europe. pp. 171–182. doi:10.1515/soeu-2021-0059.

- Dragović-Soso, J. 2002. “Saviors of the Nation.” Serbian Intellectual Opposition and the Revival of Nationalism. London: Hearst.

- Keçmezi-Başa, Sabile (2009). These Burgosurit Politike Shqiptare ne Kosovo 1945-1990: (Gjate Viteve 1945-1990 ne ish-Yugoslav Shqiptaret Kaluan ne Burgje 666 Shekuja, 72 Vjeta Albanian e 7 Muin Albanian). Logos-A. pp. 178, 368, 393. ISBN 978-9989-58-322-3. Accessed 24 August 2023.

- Organizations, Subcommittee on Human Rights and International Organizations of the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the House of Representatives of the United States Congress (1987). Persecution of the Albanian Minority in Yugoslavia: Hearing and Briefing before the Subcommittee on Human Rights and International Organizations of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Ninety-ninth Congress, Second Session, October 2 and 8, 1986. (There is practically no Albanian family in Kosovo that does not have someone in prison, including minors. The treatment of political prisoners in Yugoslavia is appalling. I will read you just one paragraph of the signed petition… (ed.). U.S. Government Printing Office. Accessed August 24, 2023.

- “The National-Chauvinist Policy of the Yugoslav Revisionists Against the Albanians of Kosovo, Macedonia and Montenegro”. Published in the newspaper “Zëri i Popullit”. Date: September 9, 1958, No. 217 (3118), p. 4.

- Lenhard, Hamza (2022). The Politics of Ethnic Adjustment: Decentralization, Local Government and Minorities in Kosovo. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-91225-1. Accessed 19 August 2023.

- AMPJ. Published 1949, Document No. 191 (B/ V-2), p. 43. “Attitudes of the Serbian authorities towards the treatment of Albanians in Kosovo and Albania.”

- Sabit Sila, p. 7.

- Sabit Sila – Institutes and Histories, Pristina. “Vendosja e puštetit yugosllav ne Kosove dhë ne viset e tjera shqiptare (1944 – 1945)”. p-6. (Translation: When the 6th Kosmet Brigade entered Mitrovica, more than 2,000 people from the city and surrounding settlements were shot. 400 dead were found in the city of Vushtrri. In November 1944, more than 1,000 people were shot from Kosovo to Tetovo, leaving the fields and pits.)

- Sabit Sila – Institutes and Histories, Pristina. “Vendosja is a Yugoslav province in Kosovo that is not under the control of the Albanians (1944 – 1945)”. p-6.

- Sabit Sila, p. 7.

- Sabit Sila, p. 8

- AMPJ, Published 1960, Document No. 530/2, p. 10. Report entitled “The Situation and Problems of the Albanian Population in Yugoslavia”, prepared by Rako Naco and Petro Papi.

- Sabit Sila, p. 10.

- Sabit Sila, p. 10.

- “AMPJ”. Published 1981, document no. 1140/1, pp. 114-115. “Report of the III Corps of the National Liberation Army of Albania”. March 1945.

- RSH), Institutes and Histories (Akademia e Shkencave e (1993). The Truth about Kosovo. Encyclopedia Publishing House. p. 198. Accessed August 23, 2023).

- A. Selmani-A. Aliu; Miderriz Haki Efendiu, “Lidhya is the History of Kosovo”. Pristina, 2005. p. 169.

- Alpion, Gezim (December 30, 2021). Mother Teresa: The Saint and Her People. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-93-89812-46-6. Accessed August 23, 2023.

- “Massacre of Bihorit in Naten and Bozhikov in 43-tes (I) – Dielli | Sun”. 5 January 2015. Accessed 23 August 2023.

- “Genocide in Bihor on Christmas Eve and Christmas 1943, according to Albanian archival documents (II)”. Dardania Press (in Bosnian). 5 January 2021.

- “Genocide in Bihor on Christmas Eve and Christmas 1943”. PRESS OF SANJAK (in Bosnian). 7 January 2016. Accessed 23 August 2023.

- Niyazi, Ramadani (2020). Shtegtim ne histori – I / Niyazi Ramadani . – Gnjilane : Rrjedha, 2020.–libra ; 21 cm. [Libri] I. – (Gnjilane ne rezistencen kombetare ne juglindje te Kosoves 1941-1951) : (studim documentary monograph. Gnjilane. pp. 277–281. ISBN 978-9951-453-02. August 2. Word. 24-24.

- Sabit Sila, p. 9.

- “Trojet e Arbri” – Albanian right wing in defense of ethnic Albania.” Published in 2006 in Prizren, Klina. pages-276-286.

- “80 years of Serb massacres in Rogovës are unknown and regrettable massacres in the institutions of Kosovo’s political elite.” Bota Sot.

- Jovan Marsijević, Hranislav Rakić, Chronology 1903-1945, Leskovac 1979, p. 185.

- Ardian, Emini (October 6, 2016). Botohet libri i autorit Preshevar Ardian Emini “Presheva ne rrjedhat e historisë” (Shek.XX). UNIVERSITIES AND TIRANES FACULTIES OF HISTORY-PHILOLOGY DEPARTMENTS AND HISTORISES. p. 85. Accessed August 23, 2023.

- Ardian, Emini (October 6, 2016). Botohet libri i autorit Preshevar Ardian Emini “Presheva ne rrjedhat e historisë” (Shek.XX). UNIVERSITIES AND TIRANES FACULTIES OF HISTORY-PHILOLOGY DEPARTMENTS AND HISTORISES. p. 111. Accessed August 23, 2023.

- S. Latifa. “Rrugetimy neper Luhyne te Preskhev”. p-78

- Petar Jochev. p. 125.

- Xhafer Shatri “Veshtrim i pergjithshem mbi politiken serbomadhe ne Kosova”. Geneva: Immigrant sa Kosova. 1987, p.91.

- Ramadani, Nixazi. Mbrojtja Kombetare e Kosoves Lindore Nga Nixazi RAMADANI. pp. 4–8, 10. Accessed August 23, 2023.

- “Persecuted and Scythians Not Kohen e Rankovikit (1948-1968) – Epoka e Re”. Accessed August 24, 2023.

- Strole, Isabel (June 30, 2021). The Yugoslav State Security Service and Physical Violence in Socialist Kosovo. pp. 110–112. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- Shefqet Dinaj Napulan. “Action and Mbledhjes Se Armeve Ne Dukagjin (1955 /1956)”. 2011. ISBN 978-1-4478-5197-4. p-43.

- Shefket Dinaj. “Action for collecting weapons in the territory of Gjakova (1955-1956)”. Faculties and Education, Universities and Prishtina, Prishtina, KOSOVO. AKTET ISSN 2073-2244. Journal of the Alb-Shkenca Institute http://www.alb-shkenca.org Reviste Shkencore e Institutit Alb-Shkenca Copyright © Alb-Shkenca Institute. p.553

- Mithat Begolli. “KRIEZINJTE E GJAKOVES”. 28. 5. 2012. ISBN 978-1-304-12767-9.

- Rifati, Rexhep (March 4, 2021). “Marreveshya e `53-tes, sforcohet me dhune nday shqiptareve ne “Periudhen e Rankovicit””. Prointegra. Accessed August 23, 2023.

- Butka, Uran (December 30, 2014). Masakra e Tivarit dhe Pergjegjesija e Shqiptar (in Albanian) (During the sending of a number of Albanians to supplement the units of the 4th Army, an incident occurred, which was not such that it could not be located, so that the consequences could be extinguished. I do not want to go into details. An Albanian jumped off the belt, took out a rifle and killed him. Then another fighter was killed. However, our other leaders, instead of solving the problem without spreading the conflict, wanted to retaliate, they tried to shoot. 40 Albanians for each fighter killed. A riot broke out. Some of the Albanians started throwing bombs. Maybe there were some bombs. And our commanders opened fire and killed 300 Albanians”. ed. note). Booktique.al. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- Hetemi, Atde (October 6, 2020). Student Movements for the Republic of Kosovo: 1968, 1981, and 1997 (Rifat Berisha was killed fighting in the Drenica Hills in 1948, and Xheladin Han was killed by the UDBA (Yugoslav State Security Service) in 1948. Rusinov, Yugoslav Experiment, 1948–1974, 25. 13. Literature on Migration in Kosovo … ed.). Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-54952-7. Accessed August 24, 2023.

- Pavlović, Aleksandar; Draško, Gazela Pudar; Halili, Rigels (June 13, 2019). Reexamining Serbian-Albanian Relations: Uncovering the Enemy (Rifat Berisha died fighting in the Drenica Hills in 1948, and Đeladin Han was killed by the UDBA (Yugoslav State Security Service) in 1948). Denison I. Rusinov, The Yugoslav Experiment, 1948–1974 (Berkeley: University of … ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-27315-2.

- Heraklid, Alexis (December 31, 2020). The Macedonian Question and the Macedonians: A History (.. where he met his death in 1951.213 This was also the fate of the main Albanian Macedonian, the young lawyer Nexhat Agoli, who was the deputy president of ASNOM and the Minister of Social Affairs.214 On the whole, however (ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-28944-2. Accessed August 24, 2023.

- Hetemi, Atde (October 6, 2020). Student Movements for the Republic of Kosovo: 1968, 1981, and 1997 (Rifat Berisha Died Fighting in the Hills of Drenica in 1948, ed.). Springer Nature. p. 67. ISBN 978-3-030-54952-7. Accessed August 24, 2023.

- Keçmezi-Başa, Sabile (2009). These bourgeois policies of the Albanians in Kosovo 1945-1990: (the Yugoslav Albanians in 1945-1990 were not worth 666 shekels, 72 years in 1945-1990) (the Yugoslav Albanians in 1945-1990 were not worth 666 shekels, 72 years in 7 months) (7 months) (only for 10 months) there is information that under the same law for criminal acts against the people… among whom was the 82-year-old Tahir Berisha.110 In this heroic battle, the brave Rifat Berisha fell.. . Logos-A. ISBN 978-9989-58-322-3. Accessed August 24, 2023.

- US Army Reserve, p. 252/I, 1951, file 340, MF 393, page 36.

- Šaban Braha. “Genocides of Serbs”. p.497-498.

- “Persecuted and Shqiptareve ne kohen e Rankovikit (1948-1968)”. PrizrenPress – Portal informativ (in Albanian). June 28, 2021. Accessed August 24, 2023.

- “Persekeutimi and Shqiptareve ne kohen e Rankovikit (1948-1968)”. DRINI.us (in Albanian). June 28, 2021. Accessed August 24, 2023.

- KOSOVO TO MAY 1997. The Origins of the Kosovo Crisis to May 1997. (In her written account, Jane Sharpe explained how Milošević came to power in the late 1980s by fomenting and then exploiting Serbian resentment towards Kosovo Albanians.[22] “While it is true that there is a long history of antagonism between the Serbian and Albanian populations,” Dr. Mary Kaldor of the London School of Economics observed that “the current crisis must be traced primarily to Milošević’s mobilization of nationalist sentiments in the late 1980s. The position of the Serbian minority in Kosovo and the insistence on the mystical significance of Kosovo for the Serbian nation were central elements of the nationalist propaganda developed by Serbian intellectuals and exploited by Milošević, using all the modern techniques, especially television, available to him.” The Serbian Information Center informed us that “the current rulers of Serbia, for their own purposes, have inflated the Kosovo myth to all proportions and turned it into a means of oppressing their own people.”[23] ed. note). Fourth Report of the Committee on Foreign Affairs. Accessed 23 August 2023.

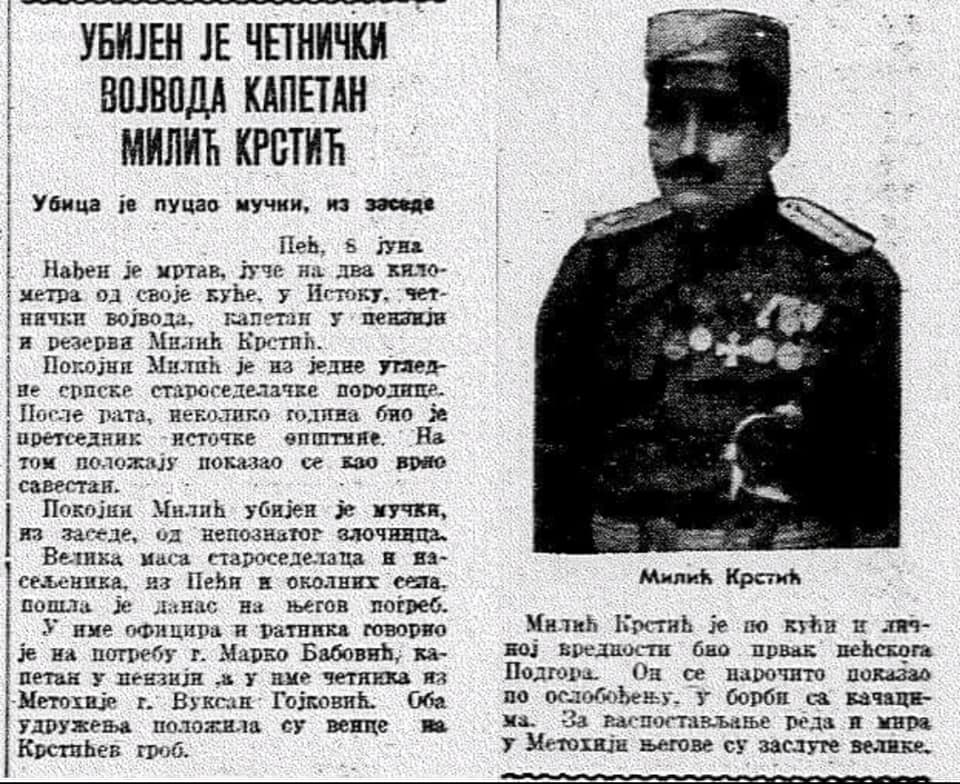

The life and death of psychopath, war criminal and mass murderer Milić Krstić

Milić Krstić or Milić Kersta (1878-1938) was a Serbian Chetnik vojvoda (captain) who emigrated during the 1900s to the Peć region of Kosovo. Krstić was responsible for the massacre of hundreds of Albanians during his military campaigns in the Istok region between 1912 and 1938. In 1924, Krstić, together with Kosta Pećanc, massacred 27 Albanians, including 5 women, in the Tutin region. Krstić also committed heinous massacres of Albanians in Llap, Uroševac, Štimlje, Dumnica, Plav and Gusinje in order to force them to leave. The Serbian government allowed the formation of separate terrorist movements such as the “Black Hand” led by Milić Krstić, a well-known criminal at the time.

In 1930, Albanian priests wrote a report on the crimes committed against Albanians, which mentioned that Krstić had killed 60 Albanians in one day in Đakovica. In 1938, Krstić was killed by an Albanian peasant named Selman Kadrija, who shot him near Lake Istok. Selman Kadrija was proclaimed an Albanian hero for executing Krstić, who was known to bayonet Albanian babies in their cradles. According to interviews with the locals of Istok, he may have slaughtered up to 9 boys from an Albanian family during one of his many visits.

Milić Krstić was also accused in 1924 of the murder of an Albanian in Rugova, and in 1927 of the murder of an Albanian from the village of Vrelska.

On June 9, 1938, the newspaper “Politika” wrote that Milić Krstić was killed 2 kilometers from his home and that he was credited with “merit for establishing order and peace in Metohija.” His war crimes were not mentioned.

References

- Krivača, Safet (28.03.2019). “Heroes and the Perbuzur Selman Kadri” . Kosovarja Magazine.

- Kabashi, Sali (July 13, 2018). “Organizations that oppose Vojvodes are the Istogut Militsa Kerrsta of Selman Kadri” . Shekulli Agency.

- Günter, Vladislav (2003). “Ochlas Valki O Kosovo V Kosovsko-Albanskych Pisnich”. Český Lid . 90 (2): 117–18. JSTOR 42639131 .

- “Haradinaj’s proposal will make the hero Selman Kadri” . RTV21 . June 3, 2019.

- 1930. Gjon Bisaku, Štjefen Kurti & Luigi Gashi: The Situation of the Albanian Minority in Yugoslavia Memorandum presented to the League of Nations http://albanianhistory.net/1930_Bisaku-Kurti-Gashi/index.html.

- “Politics”. 1938. “THE CHETNIK WARRIOR KILLED – MILIC CAPTAIN KRSTIC”.

- Kosovo per sankhakun. https://kosovapersankhakun.org/nenprefektura-e-prefektures-se-pejes-tutini/

- Selman Kadri Hasanaj. Vrasja e Milik Kerstikes. https://www.zemrashkiptare.net/news/33506/rp-0/act-print/rf-1/printo.html

- The Truth of Kosovo. “Kristak Prifti”. page 142. 1993.

- Daily Report for Eastern Europe · Issue 222–231, page 59. Link .

- SERBIAN WARS OF OCCUPATION AND OTHER MEASURES FOR THE EXPULSION OF ALBANIANS (1912-1941). Link.

- A MOTHER WOULD NEVER BRING SUCH A CRIMINAL: The infamous Chetnik spread fear in Sandžak and Bosnia, distinguished himself with bloody crimes, and then his own people LIQUIDATED him. Link .

- Ethnic Minorities in the Balkan States, 1860-1971: 1927-1938. https://www.google.se/books/edition/Ethnic_Minorities_in_the_Balkan_States_1/sgIXAQAAIAAJ?hl=sv&gbpv=1&bsq=Rougovo&dq=Militch%20Rougovo%201927&printsec=frontcover

Names of Serbian war criminals in Kosovo 1998-1999.

The following post lists the names of Serbian war criminals who killed Albanian civilians in various massacres in Kosovo during 1998-1999.

Serbian war criminals in the Djakovica massacre

Momcilo Stanojevic, Sreten Camovic, Milan Stanojevic, Rade Colic, Milan Slavkovic, Sava Stanojevic, Slobodan Kovac, Sava Stojanovic, Milan Dekic, Momcilo Dekic, Dragan Racic, Vuk Mirkovic, Vaso Vujovic, Nikotin Vujovic, Bozhi Stefik Bojan Sim, Darko Stefi Ragik Ljubisa Obradovic, Radovan Pantovic, Milic Pantovic, Aca Jovanovic, Cedomir Bozovic, Sava Jovanovic, Predrag Ristic, Goran Jovanovic, Milos Scepanovic, Srdjan Krstic, Milan Dikic, Momcilo Dikic, Zvezdan Dimic, Godjo Doka Rajkovic, Gojko Djakovic and Ladja Doka Rajkovic Lazarevic.

Serbian war criminals in the Kruše massacre Vogel

Predrag Belošević, (participant in the wars against Bosnia and Croatia), Grujica Belojević, (brother of Lubiša Belojević), Lubiša Belojević, Žarko Belošević, Žika Belošević, Mališa Tijanić, (brother and sister of Ceda Tijanik) (brother and sister of Ceda Tijanik) Ceda Tiranja Tijaniked, V. Tiranja Tijaniked, V. Tijanić, Obrad Tijanić, Živan Vučić, Mirolub Vučik, Dušan Vučik, Rade Ivanošević, (brother of Milisav Ivanošević) Milisav Ivanošević, Igor Šapić, Gradibor Radunović, Ivan Gajin and Zoran Šlanić. Most of these people were from Crkolez, while Dušan Šapić and Žarko Šapić were from Belica, and Dragan Cvetković from Uča and Slobodan Petković from Žakovo.

Serbian war criminals in the Izbica massacre

Mihajlo Tomašević, Veselin Tomašević, Slavko Tomašević, Vujadin Tomašević, Nenad Tomašević, Stojadin Tomašević, Igor Tomašević, Miloje Tomašević, Vladan Tomašević, Radoslav Tomašević, Vasilije Tomašević, Vasilije Tomašević, Tomašević Miloš, Tomašević Tomašević Miloš, Tomašević Tomašević Srgjan Tomaševik, Millorad Tomašević, Mileta Tomašević, Radenko Tomašević, Mile Tomašević, Stojadin Tomašević, Milenko Tomašević, Milan Tomašević, Dragoljub Tomašević, Gjoko Tomašević, Boško Tomašević, Zhivorad Najikidan, Zhivorad Tomaš Tomašević, Nebojša Tomašević, Nenad Tomašević, Branillav Tomašević, Ratko Tomašević, Filip Tomašević, Dejan Tomaševik, Gordan Tomašević, Predrag Tomašević, Despot Tomašević, Tadisa Tomašević, Sinisa Tomašević, Tomislav Tomašević, Zoran Tomašević, Goran Tomašević, Branislav Kragović, Ratko Kragović, (from Sirigana).

Marko Ristic, Marko Damjanovic, Dragoljub Rajkovic, Jovica Rajkovic, Rade Kovacevic-Zec, Dika Kovacevic, Ognjan Kovacevic, Gjorge Mojsic, Radosav Kovacevic-Cule, Mile Jokic, Nebojsa Kovacevic, Sinisa Ri Jokic, Svetozar Kovacfr (Svetozar Kovacfr) Momir Milentijevic, Zoran Jovanovic, Milutin Arisic, Milan Todorovic, Dejan Spasic, Nebojsa Nikcic, Miodrag Komatina, Nicifor Kovacevic, Dragan Dimitrijevic, Vukmic Lazarevic, (from Runik), Todor Deverdzik, Rade Deverdzik, S. Deverdzik, Dragisa Petrovic, Dragisa Deverdzik, Milic S. Drago, S. Ognjan Petrovic, (from Radiševo), Nenad Šmigić, Radoje Šmigić, Cvetko Šmigić, Dragan Šmigić and Golub Šmigić, (from Lečina), Dadoša Ilić, Živoin Ilić and Momčilo Radovanović, (from Kučica), Živko Joković, Radoslav Kandić, (from Kotor), as well as Radivoje Raša-Kalenović with his son Raša-Kalenović, Raša-Kalenović, Ž. Jovanović, Zoran Jovanović, Blagoje Čolaković, Nenad Čolaković, Radoš Lajović, Ilija Trajković, Rajko Rajčić, Vllado Bakracević, Lubisha Ilić, Momo Pelević, Sllagjan (former policeman), Sadudin Redžepagić from Skak, (Skak). Goran Šapić, Rade Šapić and Dušan Šapić (all three from Belica and Burimit. These names were taken from the UNMIK administration.

Serbian war criminals in Drenica

Dragisa Llazarević, Sinisa Gjorgević, Mile Blanusa, Goran Korcag, Predrag Millanović, Nebojša Radulović, Goran Simić, Saša Kostić, Slobodan Danić, Zoran Đorđević, Zvonko Šabić, Nenad Ćaušević, Z Dragih Jovanović, Milivoj Momčilović, Dejan Ivanović Janjušević, Bratislav Nedelković, Bogolub Petković, Slavolub Gjorik, Rasa Vanić, Dušan Dimik, Igor Bajrami, Zoran Alik, Jancik Branko.

Serbian war criminals in Slatina

Zoran Vukdragovic, Toger, Lubisha Simik, rreshter, Zoran Ristovski, Dusan Jevric, Zoran Jovic, Mladen Pesic, Milos Mihajlovic, Marko Zivojinovic, Slavisha Gjorgevic, Miodrag Pejatovic, Dejan Mikic, Igor Gurkovic, Ivan Stanojevic, Mile Range, Radoje Rangat, Zoran Mikic Boskic, Radoslav Ristic, Slobodan Djurdjevic, Darko Milovic, Dragisa Ivanovic, Ivan Stevic, Vladeta Stojanovic, Sasha Aksic, Nenad Jovanovic, Nenad Zivkovic, Dejan Slavic.

Serbian war criminals and their legacy, crimes committed in Kisnica

Ruždi (Bekim) Berisha, Rom, Stalin (Velko) Ilic, Pavli (Siniša) Panić, from Priština, Lubiša (Lan) Cvejić, Nga Hallak and Madh, Lipjan, Jovan (Njegoš) Vukadinović, Kuršumli, Mirko, (Draško, Dibojšk) Prilluzhe, Rade (Svetislav) Krastić, Skullan and Lipjanit, Jelica (Tomislav) Selishnik, Kishnice, Sinisha Jovanović, Kishnice, Jovan Karakhik, Kishnice, Goran Trajković, Kishnice, Boban Trajković, Kishnice, Boban Trajković, Kishnice, (Tomislav) Selishnik, Kishnice, Sinisha Jovanović, Kishnice, Jovan Karakhik, Kishnice, Goran Trajković, Kishnice, Boban Trajković, Kishnice, Boban Trajković, Kishnice, Dejan Trajnicerg, Kirag, Petar G. Trajkovic, Kirag Savelik, Kishnice, Mile Bulajik, Kishnice, Gjorge Bulajic, Kishnica, Zivorad Mitic (Ziko), Kishnica, Dragan Mitic (Burdo), Kishnica, Dragan Milic, Kishnica, Zoran Trajkovic, Kishnica, Mike Ilic, Gracanica, Dusan Ilic, Gracanica.

Serbian war criminals in Klina

Dane Balaj, Zoran Dobrik, Zarko Stepik, Vitomir Savic, Millorad Stepik, Gollub Stashik, Dragomir Stashik, Bado Bogicevik, Vojo Zaik, Sreta Dobishlevik, Vojo Dancik, Zoran Popi, Dragan Pavlovic, Radoslav Zivkovic, Radoslav Zahivkovic, Llazar Zhiv, Llazar, Radok, Shivkovic Kizic, Djoko Kizic, Nevica Dasic, Milan Krstic, Dusan Dobric, Radovan Kizic, Ranko Kizic, Golub Lazarevic, Borko Radojevic.

Serbian war criminals during the “Toges se tmerrit” massacre.

Miodrag Stanisic, Sasha Jerinic, Stanislav Vukic, Sasha Vujic, Miroslav Mihajlovic (Mikica), Millovan Ivkovic, Vidoslav Kojic, Moma Vasovic, Nenad Perzic, Branko Arizonovic, Nebojsa Stanojovic, Zoran Cvetkovic, Slavisa Maksimovic, Ar Dragisa Dinkic, Lukic Novica Sinisa Jovanovic, Aleksandar Jovanovic, Srdjan Ristic, Goran Arsic, Nebojsa Stanisic, Dragan Nojkic, Canko Spasic, Bogoso Krmarevic, Milos Mitrovic, (commander).

Serbian war criminals during the Kosovo Polje massacre

Slavisa Andrijevic, Dragomir Popovic, Boban Mitrovic, Dragan Dabizjevic, Lazar Denic, Radomir Disic, Radovan Petrovic, Dragan Mitrovic, Radojica Mitic, Dragan Ilic, Aca Stankovic, Zika Benjelavic, Mladen Lazic, Slavisa Mihajlovic, Grujic Sasha, Draga Mihajlovic, Sasha Mihajlic, Grujic Sasha Millan Milkovic, Boban Grujic, Sasha Maksimovic, Nebojsa Stefanovic, Vlastimir Jovanovic, Dusan Zarkovic, Dragan Zekic, Dobri Artinovic, Stanko Milankovic, Slobodan Mitrovic, Dobrivoje Gjorgevic, Darko Milosevic, Dragolub Lakocevic, Dragolub Lakocevic, Lubihar.

Source:

Prof. Nusret Plana. “The Terror of the Serbian Occupier over Albanians 1844-1999”. https://nusretpllana.com/products/the-terror-of-serbian-occupier-over-albanians-1844-1999

German psychologists: Serbian genocidal legacy is deeply rooted.

The Serbs as a people formed their state at the expense of the surrounding peoples, killing them, massacring them and expelling them from their centuries-old settlements. The Serbs are a people who suffered greatly from all those who were indigenous inhabitants, but lived in their vicinity. The Serbian state expanded from the Pashalik of Belgrade 30 times, plundering other people’s lands and killing and expelling the natives, and the Albanians suffered the most in that chaos.

Historically, it has never been recorded that Albanians committed atrocities and massacres against Serbs, there are even known cases when Albanians helped their Serbian neighbors! As for Serbian massacres and genocides against Albanians, they have been known and historically verified since 1887, without systematic cessation until the last war in 1998-1999.

All peoples limited to Serbs suffered massacres and genocides, starting with the Bosniaks (genocide in Srebrenica), Croats (massacre of medical staff and patients in Vukovar), Montenegrins (during the occupation in 1918, killing about 8,000 Montenegrins) who opposed the occupation of Montenegro by Serbia.

The Serbian motto for all these massacres was “the end justifies the means”, simply put, kill and massacre as much as you can to achieve the goal, i.e. the occupation and plunder of foreign territories and the expansion of the territory of Serbia. The Serbian Orthodox Church, together with the Serbian Academy of Sciences (SASA), made detailed memoranda and plans for the disappearance of Albanians from the face of the earth.

Many contemporaries who described the Serbian massacres wrote that the Serbs preferred the bayonet to the bullet for massacres, not sparing the elderly, children, and pregnant women. These inherited Serbian genocidal traits stem from the Serbian clergy, which propagates itself and its people as a divine people, meaning that it has the right to kill and maim whenever the opportunity arises, with impunity from God.

The Serbian genocidal gene has its source in their former settlements in the Carpathians and the Urals in Russia. German psychologists say that this Serbian genocidal legacy has very early roots. They emphasized that in the times when Serbs lived in the Carpathians and the Urals, they lived a difficult life and suffered from the phenomenon of “vampires”. Their relatives who died were buried and after three years were exhumed, and the bones of the head, body and limbs were ground into powder, all with the sole purpose, according to their belief, to prevent them from turning into “vampires”.

This macabre ritual does not exist among almost any other people in the world, and psychologists believe that since then this macabre genocidal trait has remained in the Serbian people. Serbian priests replace this macabre ritual with a ritual called “for the souls”. They go to cemeteries full of food and eat kins there together with the dead in order to alleviate their anger and not harm the living. The passion that this people have for killing is unprecedented. In conclusion, all Serbs who killed and massacred other peoples, instead of being punished, were declared Heroes in Serbia!

Reference

Information taken from “Albanian Kingdom, First Class Commune of Sdrečka No. 254 Sdrečka, 29th VII 1944, PT Prefecture of Prizerend”

“In connection with your order No. 1063, dated 17 July 1943, we have the honor to inform you that the detailed investigations we conducted in the territory of this municipality during the rule of Yugoslavia revealed that the following massacres were committed against the Albanian element:”

In 1923, the late Ćazim Xhemaliju from the village of Gornisele was murdered. The murder took place under the following circumstances: The victim went to visit his wife in the village of Drajčić in this municipality to his tribe, named Bajram Ademi. They went there at night, took him and led him to the Bogoshovc neighborhood in the village of Sdrečka and exactly at the place “PESOK” they massacred him, while he was tied by his hands and feet.

Names of the murderers

“The murderers are Kersto Manduš from the village of Sdrečka and Đorđe Vučković from the village of Gornišelo, together with three Serbian gendarmes. The reason for the murder stems from the fact that the Chetnik society established a headquarters in Sdrečka, headed at that time by the aforementioned Kersto Manduš.”

It is said that for the murder of this village of Sdrečka, the Chetnik society paid a certain amount of money which it handed over to the gendarmes who participated in the massacre of the victim. The victim was an Albanian idealist and was killed for that.

References

Mayor of the municipality, Sejdi Sejdorati d.v. Certified by the Chief Secretary of the Prefecture of Nika Lafe Prizren, 31 October 1944 (AQSH, fund 410, year 1944, file 58, sheet 6)

Murders in Rečan in 1912

Source: Albanian Kingdom, Municipality of Ljokovica No. 147 Ljokovica, 7.9.1943. PT Prefecture of Prizren

“Response to Order No. 1063, dated 17 July 1943”

“We have the honor to inform you that, in our previous investigations into Slavic barbarities against Albanians, we have determined that in 1912, in the village of Rečan in this municipality, the Serbian military, led by civilians Kersta Mandushi, who is still alive today, Jovan Gadžes and the Velikin family, all from the village of Sterka, forcibly took a certain Bajram Haxhi Hajdari from the village of Rečan and took him between the streets of Ljubinje and Strečka, where they cut off his lips, nose, pulled out his nails, then gouged out his eyes, and finally cut him with knives and scattered his flesh all over the world. His death from torture lasted 24 hours. The reason for his strangulation was that he was a brave and handsome man.”

That year, military forces again, on the instructions of the aforementioned Strečka, committed barbarities in the village of Rečan, taking people away and burning them, and committed several robberies of money, forcing them to pay or they would kill them.

The tortured people were: Hacı Rashit 10 Turkish liras of gold, Mustafa Arslani 25 liras, Hacı Haydar 10 liras. All of these people, after the torture they inflicted on them, were forced to hand over the aforementioned money, in addition to the looting they committed in shops and houses, taking women’s rings and earrings, prayer rugs and other valuable items. Even today, in the house of Kerst Mandushi, there is still a lamp that he stole from Zeqir Sulejman from Rečani.

There are some minor barbarities, but they are old and without facts, but the ones we described above are true, since the participants in those barbarities still live in the municipality of Strečka today.

Reference: Mayor, Fadil Xabija d.v. Verified, Chief Secretary of the Prefecture Niko Lafe, Prizren, 31. X. 1944. (AQSH, Fund 410, Year 1944, File 58, Sheet 7)

Shocking evidence of Slavic barbarity and plunder of the Albanian population between 1929 and 1930

“In the Central State Archives, folder 58 from 1944, reports sent by municipal leaders to the prefectures to which they administratively belong continue to be published, through which Serbian massacres of the Albanian population in the years from 1912 to 1930 are published. Part of this publication is also a report on the behavior of the Serbian authorities towards Albanians during their rule in the region of the municipality of Beči.”

In the first fateful days when the Serbs and Montenegrins landed in these places, they acted mildly, politely and as if they knew what the Government of Justice was thinking. But, as the old saying goes, “A wolf changes its fur, but never forgets its habit,” the conquerors of Kosovo did not go far without giving a different color to their rule. First of all, the Yugoslavs demanded the surrender of weapons and any land related to military equipment.

The local Albanians, after much animal suffering without any mercy or humanity, carried out the surrender that was demanded. Even today, when they remember this action, they are astonished. Although every weapon and ammunition was surrendered, the Yugoslav gendarmerie never had enough, it demanded new ones in large quantities, using all the means of barbarity that history remembers.

After some time, the unified government under the name “Yugoslavia” organized a group of volunteers with 2000-3000 Serbs and Montenegrins and under the command of Major Sava Lazar began to force the Albanians to change their previous religion and believe in their Orthodoxy. Sava was from Cetina. For this act, Sava beat, spat, cursed, killed, burned, fled and did everything he could to the Albanians of this region, but in vain because his goal was not achieved.

Often, hundreds and hundreds of Albanian men were tied to yard fences so that their feet did not even touch the ground, using sticks and whips, and in winter they were doused with cold water just to prevent them from changing their religion.

On the contrary, based on a clear conscience that they acted contrary to what the Slavs had ordered (that there is no lower law or morality in the world), pushing, contempt, swearing and beatings were common even from the lowest Slavs towards the Albanians, no matter how famous they were for their loyalty and generosity.

When it became apparent that the conquered Albanians were squandering everything and had nothing to give them except the land, they remembered to keep it as their own. Thus, in 1929-1930, they brought out their harsh and cruel agrarianism and began to draw borders between the lands inherited from their ancestors, at the same time impoverishing and depriving all local Albanians.

Fields, meadows, pastures, forests, pastures and every valuable land they had owned until then became the property of others. The Albanians began to become so poor that they could barely even provide themselves with daily bread, so they began to make snowballs on their land. The products were divided according to what they themselves valued before they were collected.

The wood became the property of the Albanians and these, driven by necessary needs, were forced to clear the forests and, after clearing the land of roots and stones, they had the right to take part of the stumps that they dug out of the ground and used for burning. The farmer did not immediately inform them, but this occurred again and again and always burdened the tired Albanians and increased the areas of sequestration until it came to occupying the yards of the houses up to the doorsteps.

The Serbian and Montenegrin colonists called upon the Albanians, and especially the Muslims, that their country was Turkey and that it was better for them to go there in time than to be exterminated by the Government, which, judging by the appearance, was not surprising. They raised their heads and began their brutal acts against us.

Montenegrin criminal Bulatović

Once upon a time, in the municipality of Janos, there lived a Montenegrin policeman named Bulatovic, who had the habit of going to every meeting where Albanians were present and, as soon as he entered the room, he would place his long bayonet on the tip of his rifle and drive it hard into the ceiling of the room, and no one would touch him until Bulatovic wanted to leave.

Often, gendarmerie patrols of that time would enter houses and single out with their fingers all those Albanian boys who were known for their personal abilities and intelligence, and as soon as they left the village, in the first stream or hole they found, our boys would be shot on the spot and thrown into a hole or stream wherever the conquerors wanted.

Even in the barracks, Serbian officers would often call Albanian soldiers by list and, after tying them up, would kill them with machine guns in the most heinous and insidious ways that evil human races can employ.

Source: (AQSH, Fund 410, Year 1944, File 58, pages 8-9)

Report on murders and arson committed by Serbs and Montenegrins in 1922

This year, a man named “Milić Kersta”, a Serbian guard from Istok and Peć, takes over the security of these places and forms a gang of 200-300 Serbian and Montenegrin civilian volunteers and begins to attack all of Kosovo. Milić Kersta, it turns out, set himself the goal of implementing such strict repression in Kosovo that after his departure, not a single Albanian would remain in these places.

First in this region he went to the village of Jablanica where he found the mayor of the municipality of Cermjan, the late Osman Yahja Aga from the village of Raškoc, together with his policeman named Ibrahim Kokala from Cermjan. After a loud shout, for no reason, Milić Kersta ordered his volunteers to use their rifles against every Albanian they saw in that village.

The locals, grieved by the famous barbarian, began to flee, but since they had no weapons or other means to deal with the situation, the following people were captured and shot:

Osman Yahya Aga, mayor, 40 years old, from the village of Raškoc; Ibrahim Kokala, municipal policeman, 35 years old, from the village of Cermjan.

From the village of Jablanica Qerim Binaku, 16 years old; Sil Islami, 50 years old; Haidar Islami, 60 years old; Haxhi Bajrami, 40 years old; Hysen Bajrami, 34 years old; Hashi Neziri, 38 years old; Hazir Hasani, 30 years old; Zenun Neziri, 30 years old; Ramadan Ademi, 50 years old; Hasan Shabani, 90 years old; Musli Mustafa, 70 years old, drowned in Rehma; Bajram Rama, 30 years old; Jonuz Rama, 25 years old; Ali Rexha, 60 years old; Selman Mirto, 25 years old; Tsuf Kadrija, 18 years old; Sadik Mirto, 18 years old; Ram Hamza, 30 years old; Hasan Kasemi, 70 years old; Selman Kosumi, 50 years old; Sadik Hasani, 30 years old; Sil Hasani, 20 years old; Bek Tahiri, 22 years old; Beqir Hasani, 12 years old; Avdil Zeneli, 50 years old; Isuf Zeneli, 30 years old; Kemal Keli, 40 years old; Sadik Shotani, 70 years old, burned in the fire; Zejnija of Sadik Rama, 29 years old; Ram Ahmeti, 28 years old; Fasli Muslija, 40 years old; Malik Muhajjiri, 40 years old; Yahya Karkagjija, 30 years old; Haxhi Helshani, 60 years old; Rexhep Muhajjiri, 40 years old; son of Rexhep Muhajjiri, 10 years old; Zef Zekiri, 30 years old; Niman Zekiri, 20 years old; Selim Bajrami, 20 years old; Ram Selimi, 20 years old; Ram Sefa, 20 years old; Sadik Koka, 40 years old; Kamer Sila, 40 years old; Mustafa Džema, 40 years old; Mehmet Alija, 35 years old; Haji Bajrami, 30 years old; Selim Kajtazi, 20 years old; Zach Halili, 30 years old; Hasan Redza, 50 years old.

Source: (AKSH, Fondi 410, year 1944, file 58, sheet 10)

List of persons treacherously killed by Slavs in the Suharek sub-prefecture:

Ram Blaca, from the village of Blaca, was killed by the Yugoslav state in 1927. The perpetrators of the murder were the Kostić family from Prizren and the Načanić family from Suva Reka. Isa Ademi and Fasli Baftija, from the village of Grećevac, were killed in an ambush by Slavs on April 9, 1912.

Halil Velija and Sefer Emini, from the village of Nišnueri, were killed in an ambush by Slavs on April 9, 1912.

Osman Silja, Halit Silja, Ramadan Baftjari, Šaban Silja, from the village of Vranić, were stabbed in 1912. Bajrma Faslina, from the village of Maćitava, was stabbed in Prizren with Osman Silja in 1912.

Xhel Iljazi, from the village of Maćitava, was stabbed in 1919, saying that he was holding Albanian committees.

Rustem Osmani, in 1920, Xhele Esati, in 1925, Rustem Azemi, in 1921, all three from the village of Mushtisht, were killed for no reason. Musli Dema, from the village of Vranić, in 1935, was killed for no reason. Rex Abazi, from the village of Makitava, was killed at night in 1935.

Xem Destanin, from the village of Delok, a forester, was killed in 1924, claiming to have killed Albanians. Sejdi Ram Bayraktari, from Suva Reka, in 1920 and 1927, was persecuted by the Slavs for Albanian reasons. Sadik Mehmeti, from the village of Pecan, in 1927 and 1929, was imprisoned and suffered other hardships for Albanian reasons.

The unit was confirmed by the archivist of the Sub-Prefecture of Suhareka,

Perlat Mema dv Suhareka, on 8. IX. 1944.

Confirmed by the Chief Secretary of the Prefecture

Niko Lafe Prizren, on 31. X. 1944.

Source: (AQSH, Fund 410, Year 1944, File 58, Sheet 5)

Robbery through taxes

Part of the Slavic speculation and abuse of the Albanian population was also robbery through fictitious taxes, and their increase in cases of non-payment. These taxes, of course heavy, Albanian taxpayers were forced to pay, in kind, by confiscating their livestock, but also their belongings and furniture, even their homes.

The following report by the mayor of the municipality of Junik for the Prizren Prefecture reveals a “pattern” of Slavic robberies of the Albanian population.

For non-payment of money, the relevant officials at the time prepared this plan:

They would come and ask for money at the most inconvenient times and would not want any delay in paying taxes, so they would take whatever livestock they could find, fodder for the livestock, household clothes and especially the dowries of newly married brides. The Montenegrin colonizers would sign a contract with the official, so when the goods were put up for sale, no Albanian would dare to come and buy the goods that were being sold, but those who were pre-determined would buy them for a tenth of the price.

They would give the officials a certain amount of money, and then they would take it home. Whenever a poor Albanian came with money, he would go to the one who bought the goods, who would sell them to him for ten times more than he had bought them. In this way, the dinar set aside for the tax became ten, and the tax increased every day. It happened that a person was once asked for three hundred dinars, and then when he arrived, they gave him three thousand dinars. In order to be able to get a deadline, they had to give money, a bribe, to those people who the tax collectors kept with them. Therefore, it is understandable that the person who was lucky enough to be with them, even if he was a black man, benefited a lot.

The so-called Ziber Rama, since he had a lot to pay, and there was no other way to pay, took the following things: 22 carts of hay, two boxes of women’s and men’s clothing worth 2,300 dinars. The tax collector was Milena Popoić. Hadž Ziber took a pen and a cow for 1,300 dinars.

Meanwhile, no one escaped without being subjected to such violence, just as no one escaped without being beaten in the most brutal way, so we will not go into further descriptions.

Among the worst and most cruel officials who aimed to exterminate the Albanian race were: Muj Kapiteni, who was the mayor of the municipality and whose evil deeds would require a separate book; the commander of the post, Pjetr Pjetrović, who, in order to properly punish people, said that they had weapons, and so punished them with significant fines; and Mihal Bošković.

During the destruction of Serbia, at matches held by the Montenegrins, the following died:

The wounded were Uk Lushi from the Berisha neighborhood in the village of Junik and Shaban Paleshi, as well as Sadik Jusufi and Mehmet Sahiti from the Gadzafer neighborhood, as well as Muharem Sadiku from the Çok neighborhood.

This is a brief report on the Slavic barbarities committed during the above-mentioned period in the region of this municipality.

We add that this is a hundredth part of those barbarities, but that it was completely impossible to describe all the facts in general.

Mayor of Junik,

Jah Salihi, President

of Prizren, October 31, 1944, Authorized

Chief Secretary of the Prefecture,

Niko Lafe

Source: (AQSH, Fund 410, Year 1944, File 58, Sheet 4)

Slavic atrocities in Dečani and Suva Reka and looting in Junik

Shocking evidence of the barbarities and inhumane plundering of the Albanian population by the Slavs. The barbarities in the municipality of Decani, by the Slavic elements, are both unknown and unprecedented and impossible to describe.

This is how the report of the municipality of Dečani sent to the sub-county of Đakovica in 1943 begins. The same report continues by describing Slavic crimes in the years 1912-1913, among which there was no shortage of robberies and murders, which, according to the report, “were common for Slavic monsters…”, the same report further states.

Source: Albanian State, Municipality of I Class Deçan, No. 355/2 ex 43 Deçan, dated 5. II. 1944. PT N/PREFECTURE OF ĐAKOVICA. Đeđe No. 1467/IV, dated 31. XII. 1943.

The barbarities committed by the Slavic element in the region of this municipality, during the time when cruelty ruled this country, are unknown and so unprecedented that it is impossible to describe. Robberies and murders were a common occurrence for the Slavic conspirators. Among the robberies, the Decani Church occupies the first place, which, when it set its sights on the Albanian wealth, also seized it, so its actions were always to the detriment of the Albanians.

In 1912, a Montenegrin captain, who was given the name Sav Batarja for the crimes he committed, gathered more than a thousand people in the village of Karabreg for no reason in order to frighten them and force them to drink. After the beatings began, the names of Isa Ćori, Ali Šabani, Hasan Mula, Hysen Feta, Mal Loshi, Zimber Loshi, Elez Hasani, Ibish Halili, Dak Arifi, Zek Hyseni, dared to ask about the reason for this massacre, but they all hid, frightening the people.

Those who had previously been hiding were forced to open their graves. On the same day, accused of having smuggled an Albanian, Dik Zeka was taken from Karabreg and hidden by the Montenegrins, an hour before entering Đakovica. Sadik Mehmeti from Karabreg and Azem Bećiri were also taken and hidden. This was done by the Montenegrin captain Dušan Vuković.

These murders were committed in the most barbaric manner, especially the last one in front of women and children. In 1912, simply because they were Albanians with their national feelings, they were killed by Captain Milić Krsta, Him Ahmet Iberhasaj and Rexhe Nak Dobruna from Dečani. In the same year, in the Dečani Mountains, they killed the Montenegrins Raza and Nuh Ramas with their two-year-old daughter Imer Aliu and his mother Sofa, as well as Timen and Tafa Đikoku with his son Ram Tafa and his brother, all from Dečani. There was not the slightest cause or fault in this crime. One Plavnjak was killed here, namely Taf Avdili and Ram Dostani.

In 1913, a Montenegrin named Arseni Ćirki from Belopoj abducted and killed Mr. Ram Đonin from Karabreg for no reason. Then Savo Lazar, with the help of Captain Filip Babović, engaged in robbery to the point that some were taken away alive.

These same people, for no reason, occupied and surrounded the village of Drenoc, killed and tortured people in a completely heartless manner, then the so-called Dem Tahiri, Sali Mustafa and Brahim Mustafa, after beating them, brought them in front of the village of Karabreg, threw them into cold water and left them there all night. From this torture, the above-mentioned died.