Abstract

This article examines contemporary Serbian falsifications regarding the historical identity of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg and analyzes the phenomenon of Albanian silence, described as lethargy, in response to such claims. Special attention is given to the Serbian translation and reinterpretation of Marin Barleti’s 1508 Latin biography. The study argues that there exists no credible historical evidence supporting the claim that Skanderbeg was Serbian. Rather, such assertions constitute modern nationalist propaganda aimed at appropriating medieval Balkan figures. By evaluating primary sources and historiographical traditions, the article highlights the importance of critical scholarship in resisting politically motivated historical revisionism.

Historical Revisionism and Nationalist Appropriation: The Case of Skanderbeg in Serbian Propaganda Narratives

Introduction

The debate surrounding the historical identity of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg remains a contentious issue in Balkan historiography. Recent Serbian narratives have asserted that “Skënderbeu është serb që nga kohët e lashta” (“Skanderbeg has been Serbian since ancient times”). These claims are frequently accompanied by references to the first Serbian translation of the biography of Skanderbeg, originally published in 1508 in Venice in Latin.

Such reinterpretations demand scholarly scrutiny, particularly in light of the broader pattern of historical revisionism in the region.

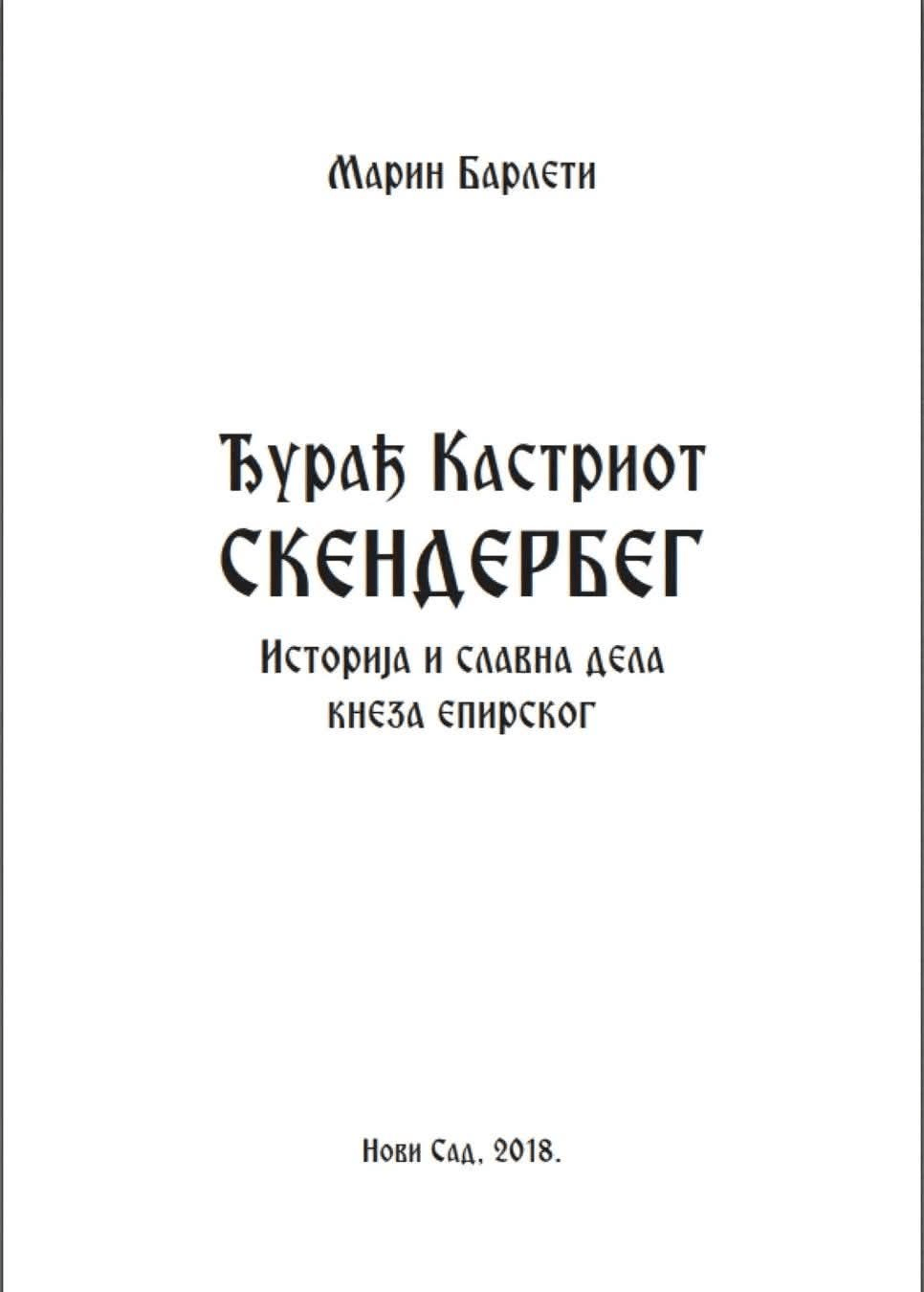

Marin Barleti and the 1508 Biography

The earliest and most influential biography of Skanderbeg was written by Marin Barleti, a contemporary of Skanderbeg. His work, Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum Principis, was published in 1508 in Venice. Barleti presents Skanderbeg as:

- Gjergj Kastrioti

- Skënderbeu

- Prince of Epirus

Barleti explicitly stated his methodological intent:

“I only wished to write the truth, for in writing about the past I do not want to produce falsehoods nor to irrationally contradict others.”

As a near-contemporary witness, Barleti’s account remains a foundational primary source. Importantly, nowhere in his work does he describe Skanderbeg as Serbian.

The Claim: “Skanderbeg Was Serbian Since Ancient Times”

The assertion that Skanderbeg was Serbian lacks credible historical foundation. No primary medieval source identifies Skanderbeg as ethnically Serbian. His family, the Kastrioti, were part of the Albanian feudal aristocracy in the region historically associated with Epirus and northern Albania.

Claims of Serbian identity rely primarily on:

- Selective interpretation of medieval political alliances

- Misrepresentation of regional administrative structures under the Ottoman Empire

- Modern nationalist reinterpretation rather than documentary evidence

There exists no archival, genealogical, or contemporaneous documentary evidence that demonstrates Skanderbeg’s Serbian ethnic identity.

Serbian Falsifications and Albanian Silence

The phrase “Serbian falsifications have not ceased; Albanian silence – lethargy” captures a recurring pattern in regional discourse. Serbian nationalist historiography has periodically attempted to incorporate prominent Balkan figures into a broader Serbian medieval narrative.

This strategy reflects:

- Symbolic competition over historical legitimacy

- Political instrumentalization of medieval heritage

- Nation-building narratives constructed retroactively

Meanwhile, the perceived lack of systematic academic response from Albanian institutions may be interpreted as intellectual lethargy. However, within mainstream international scholarship, Skanderbeg is consistently identified as an Albanian nobleman and leader of Albanian resistance against the Ottoman Empire.

Propaganda and Historical Revisionism

The claim that Skanderbeg was Serbian must be understood within the broader framework of nationalist propaganda. Historical revisionism often involves:

- Reframing medieval identities through modern ethnic categories

- Ignoring linguistic and cultural evidence

- Disregarding primary source consistency

Such narratives do not arise from new archival discoveries but from political motivations. The appropriation of historical figures is a common tactic in nationalist myth-making.

Conclusion

There is no historical evidence supporting the claim that Skanderbeg was Serbian. All reliable primary sources, including the work of Marin Barleti, identify him within the Albanian historical and cultural sphere. Assertions to the contrary represent modern nationalist propaganda rather than academically grounded scholarship.

Critical historiography demands vigilance against falsification. The integrity of Balkan historical studies depends on rigorous source analysis rather than politically motivated reinterpretation.