Abstract

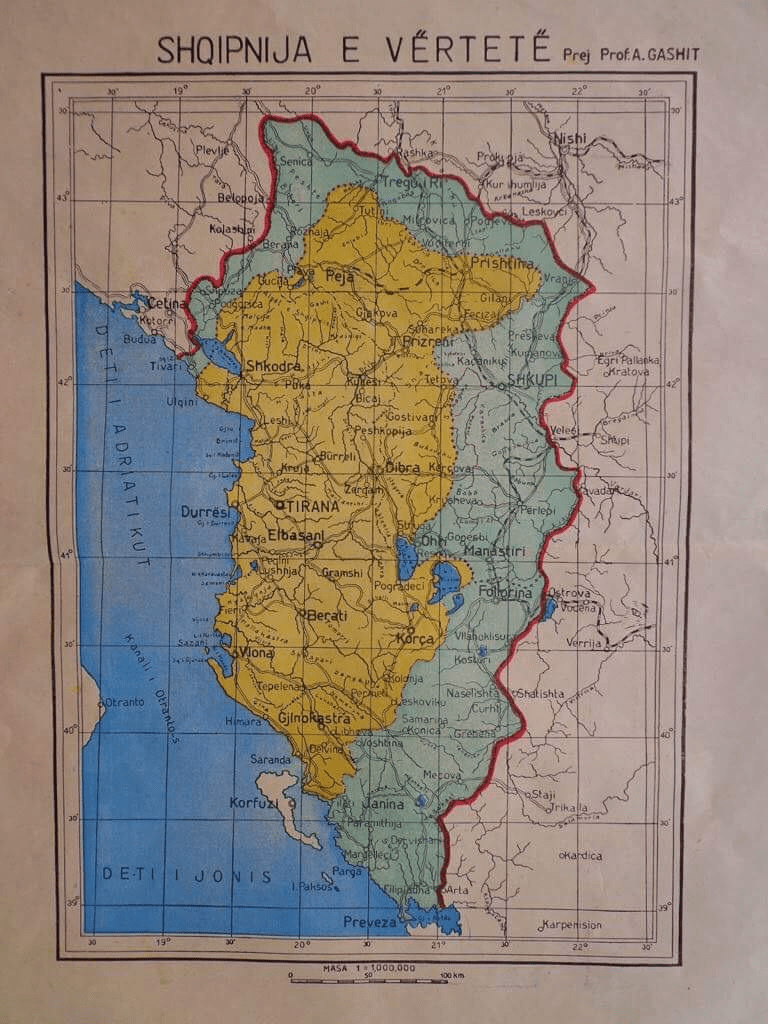

This article argues that the territorial expansions undertaken by Serbia between 1878 and 1912 came at the direct expense of Albanian-inhabited lands and populations. It examines the historical context of these annexations, the demographic and political consequences for Albanians, and the enduring legacy of disputed sovereignty in the western Balkans. From an Albanian national perspective, these territories are viewed not as legitimately integrated regions, but as lands acquired through coercion, war, and great-power diplomacy—an historical injustice that continues to shape regional tensions and identity politics.

Stolen lands and historical memory: The Albanian view of Serbia’s expansion (1878–1912)

Between 1878 and 1912, the political map of the Balkans was dramatically redrawn. As Ottoman authority receded, emerging nation-states competed for territory, legitimacy, and survival. During this period, Serbia expanded southward and westward, incorporating regions that were home to substantial Albanian populations, including areas that today form part of southern Serbia and Kosovo.

From the standpoint of Albanian historical memory and national consciousness, these annexations represent not liberation, but dispossession.

The 1878 turning point

The year 1878 marked a watershed. In the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War, European powers convened to redraw borders in the Balkans. Serbia gained new territories, including districts with long-established Albanian communities. Contemporary records and later historical research document significant expulsions of Albanians from these areas, particularly from regions such as Niš and its surroundings.

For Albanians, this period is remembered not simply as diplomatic realignment, but as the beginning of demographic engineering. Thousands were displaced, villages were emptied, and a pattern was set: territorial expansion accompanied by population transformation.

The Balkan Wars and the incorporation of Kosovo

The Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 further altered the balance. Serbian forces entered Kosovo and other Ottoman-administered lands with majority Albanian populations. The incorporation of these territories into the Serbian state was celebrated in Belgrade as national unification. Yet among Albanians, it was experienced as military conquest.

Reports from international observers at the time described violence, reprisals, and efforts to consolidate control through force. Whether interpreted as the chaos of war or systematic policy, the result was clear: a population that had not identified as Serbian was now governed by a state it had not chosen.

Competing national narratives

Serbian historiography often frames this era as the restoration of medieval Serbian lands and the liberation of Christian populations from Ottoman rule. Albanian historiography, by contrast, emphasizes demographic realities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, arguing that many of the annexed areas were predominantly Albanian at the time of conquest.

These opposing narratives are not merely academic disagreements; they form the emotional and ideological backbone of contemporary politics in both Serbia and Albania, as well as among Albanians throughout the region.

Why the question persists

More than a century later, the issue remains unresolved in the realm of identity and historical justice. Even where borders are internationally recognized, the perception of illegitimacy persists. For many Albanians, the territories annexed between 1878 and 1912 were never freely ceded, never fairly negotiated, and never morally transferred. They are seen as lands taken during a period of imperial collapse and great-power opportunism.

The argument that these territories “remain and will always remain stolen” is less a legal claim than a moral and historical one. It reflects a belief that sovereignty imposed by force cannot erase collective memory, nor extinguish claims rooted in demographic presence and historical continuity.

The enduring impact

The legacy of these annexations continues to influence political discourse, interethnic relations, and regional stability. Competing historical interpretations shape education systems, commemorations, and diplomatic rhetoric. They also complicate reconciliation efforts, as each side views the past through a lens of either liberation or loss.

If peace in the Balkans depends on mutual recognition of historical suffering, then acknowledging the Albanian experience of 1878–1912 is essential. Whether one agrees with the characterization of “stolen territories” or not, it is undeniable that for many Albanians, these lands symbolize unfinished history—territories incorporated by force and remembered as unjustly taken.

Bibliography

Blumi, Isa. Reinstating the Ottomans: Alternative Balkan Modernities, 1800–1912. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. New York: Harper, 2013.

Elsie, Robert. Historical Dictionary of Kosovo. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2004.

Judah, Tim. Kosovo: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Malcolm, Noel. Kosovo: A Short History. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

Misha, Piro. “Invention of a Nationalism: Myth and Amnesia.” In Albanian Identities: Myth and History, edited by Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers and Bernd J. Fischer, 33–48. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

Pavlowitch, Stevan K. Serbia: The History Behind the Name. London: Hurst & Company, 2002.

Rama, Shinasi A. Nation Failure, Ethnic Elites, and Balance of Power: The International Administration of Kosovo. Cham: Springer, 2019.

Skendi, Stavro. The Albanian National Awakening, 1878–1912. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967.

Vickers, Miranda. Between Serb and Albanian: A History of Kosovo. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.