by Ethem Ruka.

Summary

Set in the 18th century under Ottoman rule, The Legend of Mirua of Tërbaçe tells the story of Miro Kostë Strati, the sister of Skëndo, who is killed by an Ottoman tax collector after refusing to pay oppressive taxes in the village of Tërbaçe. Skëndo’s death sparks Miro’s transformation from a grieving sister into a fierce avenger. Disguised as a man, she embarks on a journey to Vlorë, where she seeks out and kills the pasha responsible for her brother’s death. Her act of revenge turns her into a legendary figure, immortalized as a symbol of resistance and bravery.

It was just past the middle of the eighteenth century.

Poverty reigned throughout the Albanian lands. The rise in taxes had turned into a rope that tightened daily around the necks of the people under the rule of the Ottoman Empire.

The peasants, who could barely feed their families with corn bread and wild cabbage, were forced to pay taxes on production, land rents, extraordinary duties in times of crisis, and additional burdens if they were Christian. The obligations grew relentlessly, while their tables grew increasingly barren.

Heavy taxes not only opened new wounds in the lives of the people but often led to armed clashes. As one rebellion in a region of Laberia was quelled, another would erupt elsewhere. The captains of those times stood at the forefront of these confrontations, ready to give their lives to defend the honor of their land.

The Vlorë River had become a major problem for the Ottoman tax administration. Tax collectors returned empty-handed from these areas. Refusal was open and resistance was firm.

“We will crush them with force,” declared the sub-governor of the Vlorë Sanjak. “If they don’t pay their dues, they will curse themselves,” added this heartless pasha.

Soon, the punitive expedition accompanying the tax collector set off towards the Vlorë River. They left before dawn, but with the worry that they were entering a dangerous area where guns and yataghans knew no fear.

The tax collector was a tall, imposing man, dressed in a long, dark coat that reached below his knees. Around his waist was a wide belt where he hid papers, seals, and perhaps a small weapon. He always carried his staff, a symbol of power and fear.

He decided to start with Tërbaçe, the village most rebellious against the taxes. The column reached the base of the hill leading to Tërbaçe, where the mountain and the Shushica valley merge. As soon as he dismounted from his horse, he approached the first man who came his way, Skëndo Strati, a tall man with a stern face.

The tax collector asked for water, and Skëndo, following local custom, brought him a jug of fresh water. As the tax collector gulped the cold water, he asked Skëndo why the people of Tërbaçe were refusing to pay their taxes to the Empire. As soon as he heard these words, Skëndo’s face darkened like a winter day. He did not allow the newcomer to continue.

“If you’ve come for the taxes, aga, better turn back the way you came without wasting any more time,” he said. The refusal was open. The authority of the Empire felt challenged. Offended and consumed by anger, the tax collector gestured with his hand. A guard hidden behind the bushes raised his weapon and took aim. The gunshot split the air and the echo reached the gorges leading to the peak of Mount Çika.

Skëndo fell to the ground. A river of blood soaked the dry earth. He tried to rise, but his body failed him, and he closed his eyes forever.

“To these treacherous Albanians, not even a bullet can take their life,” muttered the tax collector with bitterness, as he hurriedly mounted his horse. “Quickly! We must leave. We’ve taught them a lesson. The others will understand that one cannot mock the Empire,” said the tax collector urgently.

News of the tragedy spread to every house in Tërbaçe. The young and the old gathered to escort Skëndo with wailing and dirges to his final resting place. The one who never shed a tear was his only sister, Miro Kostë Strati, or as the villagers called her, Mirua of Tërbaçe.

For Miro, this was yet another drama. She had lost her father, a nizam in the far deserts of Arabia, and today, she was losing her only brother. Orphaned as children, they had supported each other as two branches of the same root.

For Miro, Skëndo’s death was not just the loss of a brother, but the collapse of the pillar that had kept her standing all her life.

On the day of the burial, amidst the crying and sorrow, Miro swore quietly. Although a woman, she decided to avenge her brother and all those punished for their rebellion against the invaders. Her grief turned into an uncontrollable hatred that would not cease until blood was repaid with blood.

From that moment, Miro of Tërbaçe became a part of legend.

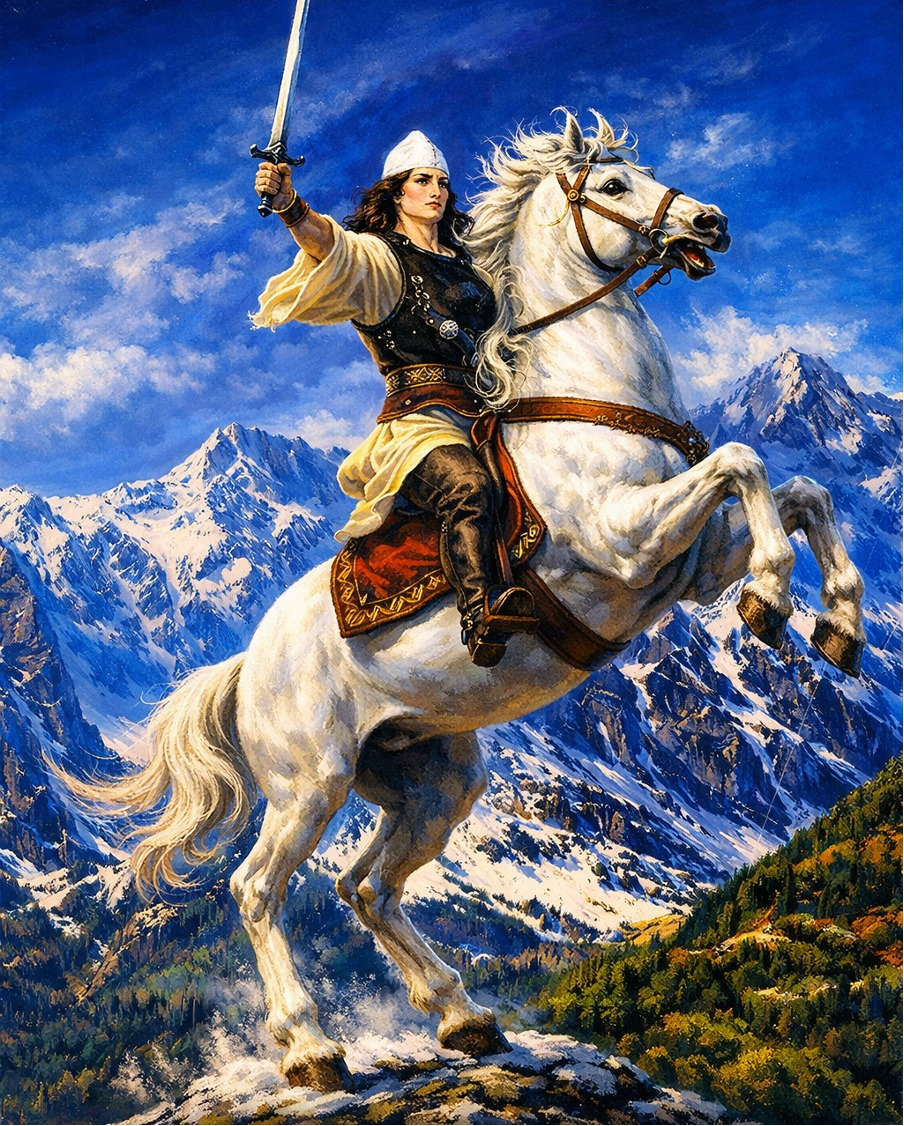

She didn’t wait long. The next day, she dressed as a man, gathered her hair and tucked it deep under her headdress. She took the pistol and yataghan, mounted her white horse, and headed towards Vlorë. The boys of Tërbaçe did not leave her alone but became her wings.

The first thing she did in Vlorë was to go to the barber to have her hair cut. And the rhapsodist carved verses that would never be forgotten:

“O barber, my brother,

I have a problem, said Mirua,

I want my hair cut,

Like a boy, groom me…”

At that time, the Vlorë Sanjak included not only the city with its port but also the Vlorë River region, Kurvelesh, Himara, part of Mallakastër, and the villages of all of Laberia.

No matter how protected he felt by the garrisons under his command, the sanjakbey knew very well that one bullet in a dark alley could end his life. A heavy premonition gnawed at him: the people of Tërbaçe would not forgive the bloodshed. Disturbed, he decided to secretly leave for Mallakastër and stay there until the anger of the Labërs subsided.

All of Miro’s and the boys of Tërbaçe’s efforts to find him in Vlorë failed. But a woman’s intuition rarely betrays her. Miro headed toward the palace in Mallakastër.

The heavy door remained closed and the guards controlled every entrance and exit. Miro went directly to the gate and told the guards she had an urgent ferman that she needed to deliver to the sub-governor personally. The guards believed her and notified the sanjakbey.

He slowly descended the palace steps. Miro found herself face to face with him. It was the right moment. Miro pulled out the pistol. “The first bullet is for my brother whom you killed treacherously. The second is for my father who died young in the deserts of Arabia.”

Two gunshots rang out and the heavy pasha fell to the ground. Her vow was fulfilled, and the people once again sang:

“She pulls the pistols from her belt,

And the Pasha she sets alight,

One in the heart, one in the head,

Leaving him dead upon the ground.”

Miro fulfilled her vow and felt relieved. She leaped like lightning onto her horse and returned like an eagle from where she came. They followed her but couldn’t catch her. The legend says she ended her life with her uncles in Dhëmblan, Tepelena.

Mirua of Tërbaçe became a spirit of bravery that roamed the mountains of Laberia. The people turned her into a legend, and legends have the privilege of never dying.